In this post, we unpack the history of the cannabis plant, and the FSSAI’s acknowledgement of cannabis derivatives under the category of food.

What’s legal but seems almost illegal? For the investors on Shark Tank India[i], it’s hemp businesses. While, there’s not much that hasn’t already been said about the TV show, but there’s a lot to be unpacked about the Food Safety and Standards Authority (FSSAI) of India’s recent acknowledgement of the industry.

There has been a lot of chaos and uncertainty around the use, sale and cultivation of cannabis. But with regulators like the FSSAI taking the high road to regulate the hemp industry, the future looks bright. In this post, we unpack the universe of the cannabis plant, FSSAI’s new regulation and then some.

What’s in a name? Bhang vs. Ganja vs. Charas

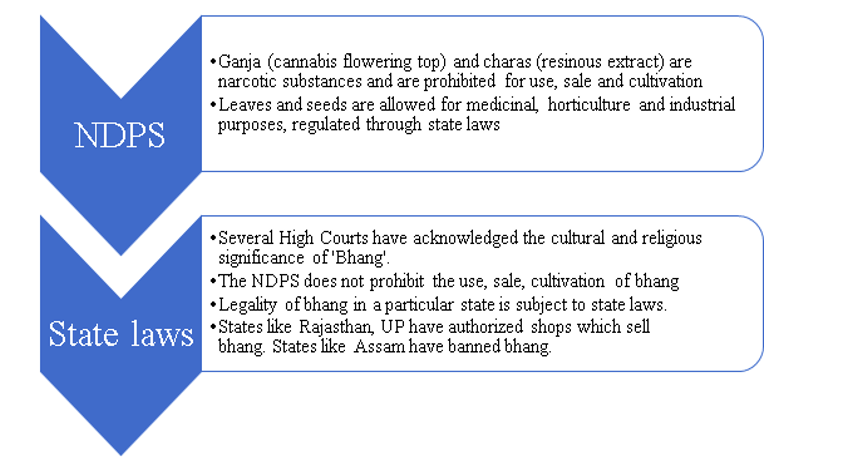

In India, cannabis derivatives have been historically used in three main forms – bhang, ganja and charas[ii]. Bhang is the matured leaves or fruit of the plant, and has legally been allowed for use in the country. Ganja, is derived from the flowering tops of plant, and charas is the resinous extract of the plant. Both of which are prohibited for use under the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985 (NDPS)[iii]. The cultivation of the bhang, leaves and seeds is regulated by the state governments.

Source: Ikigai Law

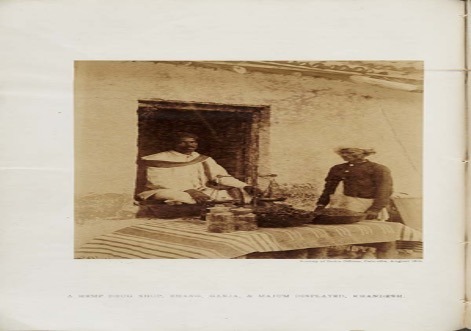

Hemp is a derivative of cannabis, and is primarily cultivated for industrial use[iv]. Under colonial rule, where other substances like opium were illegal, cannabis derivatives were not banned outrightly. The British government deliberated[v] that a ban was likely to cause social unrest, and decided to tax it instead. Cannabis also finds mentions in Ayurveda text as ‘vijaya’ and has been recommended for its medicinal properties. Ayurveda literature like Charaka Samhita mentions properties of Vijaya as digestive and intoxicating[vi]. Which makes the cultivation and usage of the plant a religious and cultural phenomenon.

Source: The Indian Hemp Drugs Commission Report,1894. This was an Indo-British study of cannabis usage in India. In the world’s most thorough report on cannabis, the British government decided to tax cannabis instead of banning it.

Unpacking science

Before we delve into how the FSSAI regulates hemp, it is important to understand what it regulates.

Cannabidiol (CBD) and delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) are the two important chemicals found in cannabis. There’s a biological pathway in your body called the endocannabinoid system that helps regulate your mood, appetite, sleep, memory and pain sensation. Both THC and CBD hijack this system, but in different ways. THC initiates a psychological response in your brain and has ‘psychotropic’ effects. Think – pleasure, euphoria, relaxation. CBD, the non-psychoactive component, may have an effect on your body instead. Think – pain, fatigue, appetite. So, between the two, it is THC that can make you ‘high’ in the conventional sense[vii].

And?

Now, several regulators across the world have attempted to regulate these components. The THC content in industrial hemp regulated by the US law prescribes a threshold of 0.3% or less. For medical cannabis, the percentages may hover over 3% and can be up to 10-15%[viii]. In India, the Uttarakhand drug regulator also limits the threshold of THC for cultivation to up to 0.3 %[ix]. This seems to be borrowed from US’ Agriculture Improvement Act, 2018. However, given there are no such thresholds in the NDPS Act or any other Indian guidelines, there’s not much to be said about how this actually plays out.

The previously hesitant FSSAI has now issued guidelines for the hemp industry

India is among one of the countries that voted in favor of the recommendation to remove cannabis from the ‘strictest control’ Schedule at the World Health Organization Commission for narcotic drugs, noting its medicinal and therapeutic benefits[x]. And in line with that sentiment, the FSSAI emerges as an aide to the hemp industry. This is the industry that makes your hemp powder, tablets, tote bags, oil and maybe even hemp sparkling water!

In 2017, the FSSAI issued notices to hemp manufacturers, highlighting that the sale of such products under the FSSAI label is illegal.[xi]. But 4 years and a couple of successful hemp businesses later, it has come around. On 15th November 2021 it recognized hemp seed and hemp seed products as ‘food’[xii]. The notification regulates and allows for sale of products derived from ‘non-viable seeds of the cannabis sativa/other indigenous cannabis species’. And the cultivation has to, as usual, comply with the NDPS and state laws.

Interestingly, it chalks out limits on THC and CBD levels. It says, hemp seeds from plants that have less than 0.3% THC are allowed to be used as food products. TheTHC levels shall not exceed 0.2 mg/kg in any beverage. And, CBD levels shall not exceed 75 mg/kg. It also specifies that children under 2 years cannot be administered hemp products. The other major takeaways from the notification include caveats on labelling and advertising. Sellers can’t- (a) market their product as having psychoactive effects; (b) use an image of the cannabis plant (except the seed) on the product’s label (that makes almost all of the labels we see in the market, contentious).

Way forward

This is a step in the right direction, but regulating this may require more deliberations around setting quality standards, labelling practices, promoting consumer education and considering the interplay with NDPS and Drugs and Cosmetics Act 1940 (DCA), among other things. Presently, there are a few hemp companies that operate with an AYUSH license, regulated by the DCA, some of which are also recognized by the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade. However, with the existing regulatory uncertainty and overlap, policy deliberations are at the core of this industry.

All things considered, it wouldn’t to be too incorrect to say that the value of cannabis is slowly ‘hitting’ the government.

This post has been authored by Aparna Sridharan, Associate, with inputs from Anirudh Rastogi, Managing Partner at Ikigai Law.

Image credits: Pixabay

[i] https://www.sonyliv.com/shows/shark-tank-india-1700000741/india-hemp-and-co-s-pitch-1000154025

[ii] https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/bulletin/bulletin_1957-01-01_1_page003.html

[iii] Section 2(iii) of the NDPS.

[iv] Industrial use means cultivation for the purposes of food and beverages, personal care products, nutritional supplements, fabrics and textiles, paper, construction materials, and other manufactured and industrial goods. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R44742.pdf

[v] https://indianculture.gov.in/report-indian-hemp-drugs-commission-1883-94

[vi] http://t27.ir/Files/121/Library/6098f709-0ba3-4096-adf3-db94e4454b6f.pdf

[vii] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3736954/#:~:text=and%20their%20differences.-,Delta%2D9%2Dtetrahydrocannabinol%20and%20cannabidiol,both%20in%20animals%20and%20humans.

[viii] https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-regulation-cannabis-and-cannabis-derived-products-including-cannabidiol-cbd

[ix] https://www.livemint.com/news/business-of-life/cannabis-firms-aim-high-despite-the-legal-haze-11615133915697.html

[x] https://indianexpress.com/article/india/un-decides-cannabis-not-a-dangerous-narcotic-india-too-votes-to-reclassify-7089562/

[xi] https://archive.fssai.gov.in/dam/jcr:b4d5fb0b-a32a-47cb-aaa9-4866dc04e80b/Letter_Hemp_Seeds_18_10_2017.pdf

[xii] https://www.fssai.gov.in/upload/notifications/2021/11/619b553646e10Gazette_Notification_Oil_Flour_22_11_2021.pdf