This post dives into the trade margin rationalisation approach for price regulation of medical devices, and suggests ways to increase transparency while using the approach.

Background:

In July 2021, the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority (Pricing Authority), through a notification (July 2021 notification) announced that it would regulate the prices of five medical devices: (i) pulse oximeter; (ii) blood pressure monitoring machine; (iii) nebuliser; (iv) digital thermometer; and (v) glucometer.[1] This move was made against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic and aimed at ensuring affordability of these medical devices.

The Pricing Authority is empowered by the Drugs (Price Control) Order, 2013,[2] to control the prices of drugs and medical devices. In this case, the Pricing Authority has regulated the maximum retail price of the five medical devices listed earlier, using the trade margin rationalisation approach (TMR approach).

The Pricing Authority has in effect, put the medical devices industry on a diet, that determines how much money the industry can make on these five devices. For the purposes of tackling the pandemic this was a sensible move, but it does raise some long-term questions on India’s drug pricing policies. In this article, we deconstruct what trade margin rationalisation is, and what the Pricing Authority and medical device industry need to consider, while using the TMR approach to regulate prices of medical devices, going forward.

Understanding the links in the medical device supply chain:

Medical device companies incur various costs for innovation, manufacturing/importing, and selling medical devices. The supply chain is long, with many entities playing a role in getting the medical device to the end consumer (i.e., the patient).

Think of each link in the chain as an added layer of inputs and costs. Each input in making the medical device adds on to the overall cost of the medical device. This will ultimately affect what price the medical device is sold to the patient. For instance, chips and semiconductors are key components of medical devices. Procuring them will include the cost of procuring and transporting it from the manufacturing unit to the port, followed by shipping the product to the importing country. There will be labour costs for coding the chip in the medical device.

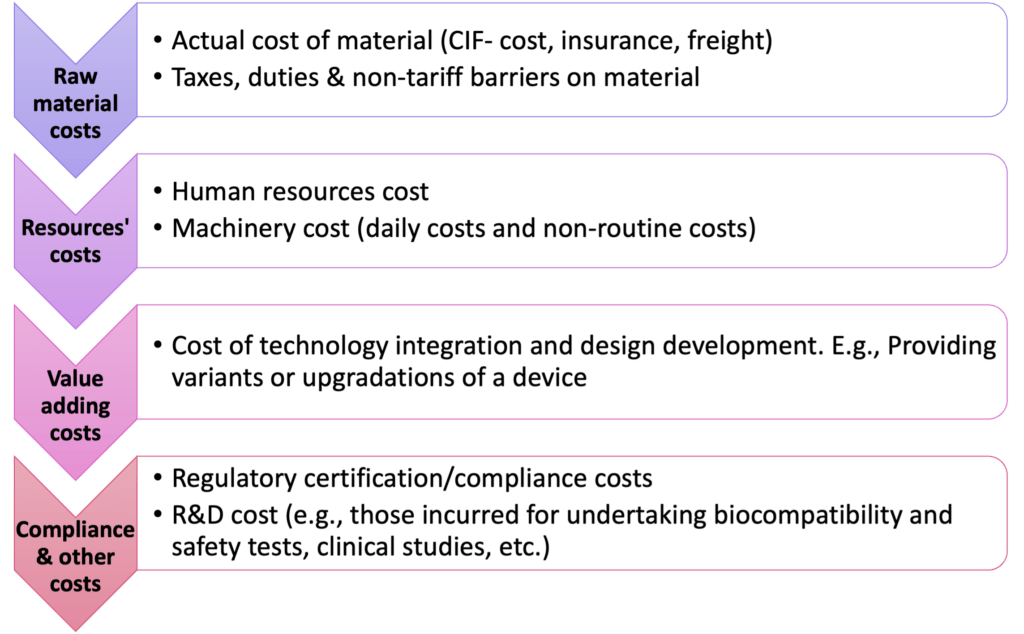

The figure below describes what costs are typically added through the medical device supply chain:[3]

Figure 1: Costs involved in manufacturing/importing a medical device.

Trade margins and trade margin rationalisation explained:

The Pricing Authority, therefore, has to balance affordability for the patient with profitability for the manufacturers. One way is to use ‘trade margins’ to help moderate the costs involved in making/importing the medical device, and consequently determine the price of the medical device for the patient (i.e., the maximum retail price of the medical device).

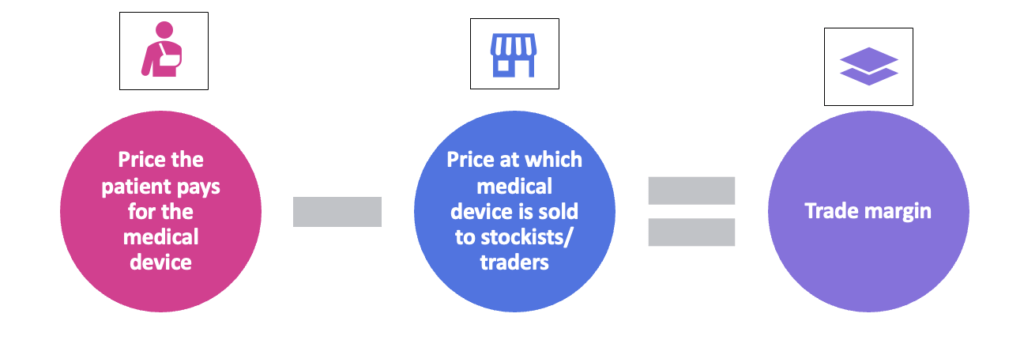

Figure 2: What is a trade margin?

In India, the conversation between the healthcare industry and the government on using trade margin data to rationalise the price of medical devices and drugs began in 2017 and resulted in a consultation paper from the Niti Aayog titled ‘ Rationalization of trade margins in medical devices – a consultation paper’.[4] The Niti Aayog consultation paper states that trade margin is the difference between the price to patients (i.e., the maximum retail price) and the price at which the manufacturers sell the drugs/devices to distributors (i.e., the price to trade).[5] For instance, ABC Technology Ltd., sells its blood pressure machine, at INR 2000 to a wholesaler, and the wholesaler then sells it to the patient at INR 3000. The trade margin here is INR 1000.

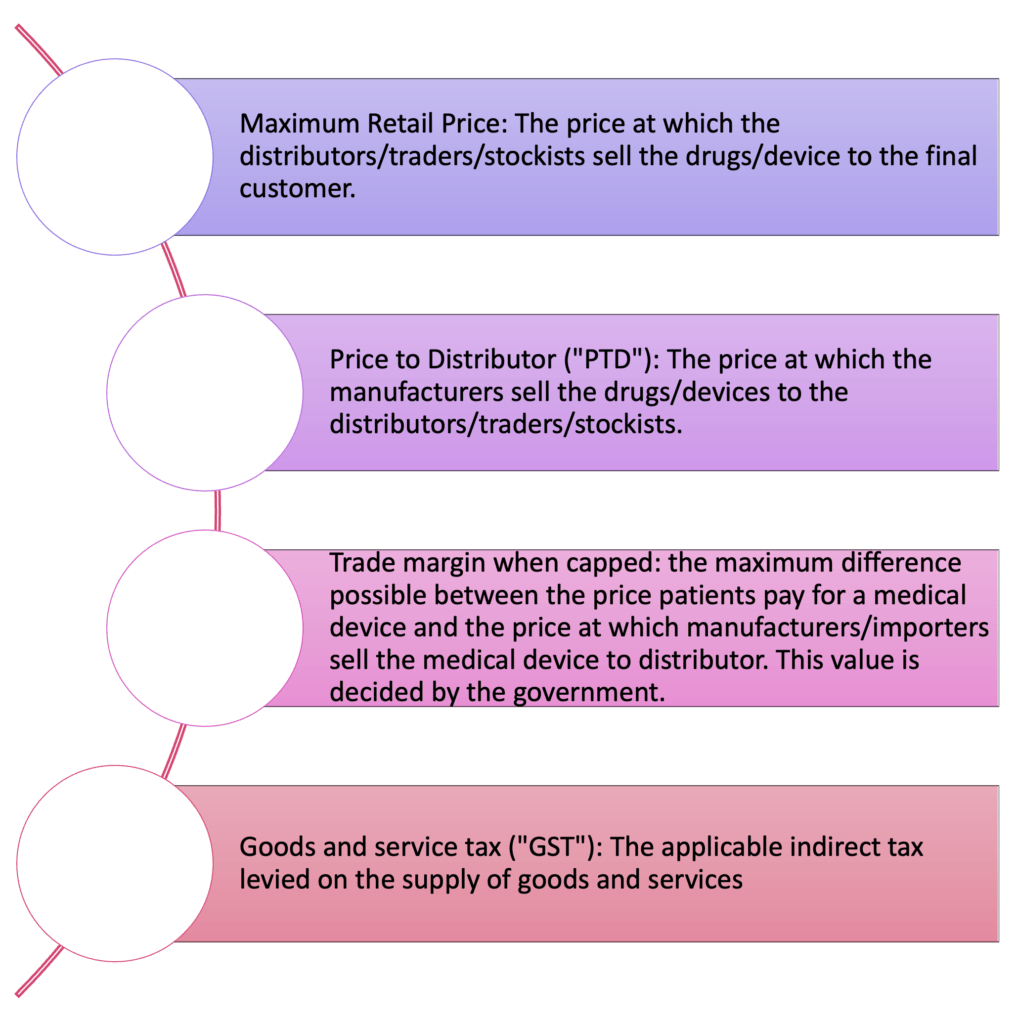

The figure below provides a glossary of terms that are key to calculating the maximum retail price of the medical devices to patients via TMR:

Figure 3: Glossary of terms

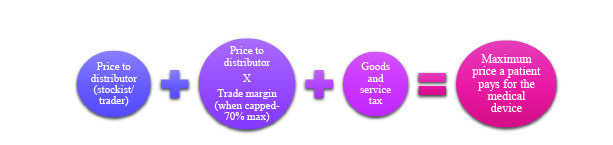

What is trade margin rationalisation?

Trade margin rationalisation basically puts all entities in the supply chain on a diet, where each entity has to reduce their fat intake (i.e., their costs), so that the final cholesterol reading (i.e., the price of the medical device) is within medically accepted parameters (i.e., the price is under control). Here, the authority setting the medically accepted parameters is the Pricing Authority. Trade margin rationalisation involves capping the trade margin and using the capped trade margin in calculating the maximum retail price of the medical device.

The Niti Aayog consultation paper suggested that a cap in the trade margin should be decided by the government of India. At present, the Department of Pharmaceuticals decides the cap on trade margins.[6] One of the key considerations in this decision on what is the point of first sale (i.e., the point where the diet starts). The trade margin is usually calculated from this point of first sale. Currently, the Pricing Authority has decided the point of first sale to be the price paid by importers/manufacturers to distributors of the medical devices. The Pricing Authority has also placed the cap on the difference in the prices to stockist and to patient (i.e., trade margin when capped) at 70%. The Pricing Authority currently calculates the maximum retail price of the five medical devices listed above using the TMR approach with the following formula:

Figure 4: Formula for calculating the maximum retail price using the trade margin rationalisation approach

In a trade margin rationalisation paradigm, if ABC Technologies Ltd., decided to increase the price of its blood pressure machine to INR 3000, it will need to see how that affects what entities further down the supply chain can add as costs.

The diverging views of the medical device industry in India:

There are divergent views on where the point of first sale should be, as acknowledged by the Niti Aayog consultation paper.[7] Some Indian medical device companies[8] believe that the point of first sale for importers should be the point where the medical device enters India (i.e., the landing price). Some even suggest that the ‘price to distributor’ should not be considered the point of first sale; adding that for domestically manufactured medical devices the trade margin rationalisation should be done based on the selling cost of goods from a seller’s factory (i.e., “ex-factory price”).[9]

Some medical device importers, on the other hand, favour the point of first sale being the point at which the trade margin is calculated from.[10] This is because if the maximum retail price is decided based on when the medical device enters India (i.e., the landing price), such a price will not account for the costs incurred by the importing company on issues such as training of healthcare professionals, product liability, technical product support, and instrument handling.[11] Both Indian manufacturers/importers and foreign medical device manufacturers/exporters question how the government will decide the cap on trade margins.[12] However, there are Indian medical devices companies that feel this form of computation is a step in the right direction.[13]

Industry thoughts on the TMR approach can also be seen in the recent Competition Commission of India’s (CCI) market study on the pharmaceutical sector. The CCI surveyed the industry, who noted the challenges of applying the TMR approach to all products. One challenge is that doctor may prescribe drugs that are not price regulated through the TMR approach. In such a scenario the drugs they prescribe may actually be priced higher than the drug being controlled using the TMR approach.[14]The CCI therefore recommended that more studies be conducted before the TMR approach is expanded to other therapeutic areas (i.e., beyond cancer drugs and medical devices related to COVID-19 management).[15]

Taking a leaf out of international best practices on price control to achieving greater transparency:

The Pricing Authority’s July 2021 notification suggests that the five medical devices up for price control, had trade margins of 709%.[16] The lack of clarity on what data sets the government used to arrive at the 709% figure, and further the cap on trade margin at 70% has been pointed out by the industry.[17]

One method of making the TMR approach more transparent can be by adopting some of the guidelines released by the World Health Organisation on countries’ pharmaceutical pricing policy. The World Health Organization’s ‘Guidelines on Country Pharmaceutical Pricing Policies’ (WHO Guidelines 2020),[18] provides a set of recommendations on how countries can approach price control: (i) regulation of mark-ups (i.e., price increases) in the pharmaceutical supply and distribution chain; (ii) use of internal reference pricing (referencing to similar drugs available within the territory of the country, for example, biosimilars and generic drugs); (iii) application of cost-plus pricing formulae (i.e., using manufacturing costs plus a few additional costs) for pharmaceutical price-setting; (iv) use of external reference pricing (referencing to pricing in other jurisdictions); (v) promotion of use of generic medicines.[19]

The WHO Guidelines 2020 suggest further measures under these guidelines. For instance, while referring to pricing data from sources that are external or internal to the country, the pricing data must be from verifiable data sources.[20] External price referencing must be done ‘in conjunction with other pricing policies, including price negotiation’. Internal price referencing must be done ‘in conjunction with policies to promote the use of quality-assured generic or biosimilar medicines’.

Similarly, the WHO Guidelines 2020 recommend the following conditions, for countries that opt for mark-up related policies (like the TMR approach in India): (i) mark-up policies should be done along with other pricing policies; (ii) the mark-up structure should allow for the mark-up rate to decrease as the price of the medical device increases (i.e., regressive policy) rather than using a fixed percentage mark-up for all prices. Based on this, the Pricing Authority should reconsider its use of a fixed percentage of 70% to cap trade margins This will help companies compete in the Indian market and also ensure that quality is not compromised as a result of the supply chain diet.

Norway appears to follow the WHO Guidelines 2020. It refers to pricing data from other countries to make its drug pricing decisions; having a much more detailed process to fix price caps for prescription drugs. Although, medical devices are kept outside the realm of such price control, the Norwegian process provides clarity on one criticism of the TMR approach. That is, why are the margins set at the value that they currently are? The Norwegian Medicines Agency (NoMA) caps the maximum price for all eligible medicines. All sellers must apply for a maximum price. The maximum price consists of two elements; (i) maximum pharmacy purchase price (“PPP”), or what the drug costs to the pharmacy; and (ii) the maximum pharmacy retail price (“PRP”), or what the drug costs to the customer. The PPP is arrived at by[21]

- International price comparisons-The PPP is set as the average of the three lowest market prices in relevant European Economic Area (EEA) countries;

- The prices of comparable medicines including biosimilars and generics;

- The costs of production.

PRP is decided by adding PPP and a maximal profit for the pharmacy. The maximal profit for prescription drugs entails: (i) 2.0% add-on from the PPP; (ii) 29.00 Norwegian Krones added-on per package (iii) 0.5% add-on from the PPP if the prescription medicine requires temperature control (i.e., cooling); and (iv) 19.00 Norwegian Krones added-on per package for medicines that may be addictive.

The takeaway:

The Pricing Authority’s current use of the TMR approach misses addressing several procedural and conceptual ambiguities such as – what datasets does the Pricing Authority use to compute margins? Are these data sets verified? What other considerations have been taken into account to reach the trade margins?

Working with the Pricing Authority is the only way to ensure that the diet is fairly distributed across the supply chain, and that access to quality healthcare is safeguarded. The medical devices industry can support the Pricing Authority by:

- Providing a breakdown of costs of production/import to the Pricing Authority. For example, incase of technology backed medical devices, a link in the supply chain may be periodic subscription payments to technology tools (e.g., AI/ML tools, cloud service providers, etc.), to offer uninterrupted services to the patient. It could include data on sourcing technical components of the medical device like chips and semiconductors and costs involved.

- Providing greater context to be used while interpreting external or internal data sets. For example, there is evidence that relying on external price referencing alone may in the long term hinder access to medical products. In such cases, the industry can point to the WHO Guidelines 2020, which call for mark-up related policies to be done in tandem with other pricing policies.

Inputs such as these will help the Pricing Authority arrive at caps on trade margins based on verifiable data sets. Additionally, the industry can present evidence on where the trade margin should start getting calculated (i.e., the point of first sale). Therefore, transparency will be increased because (a) the data sets relied on will be known; and (b) the industry will have a chance to engage with the Pricing Authority, with greater specificity.

This piece was drafted by Shambhavi Ravishankar and Aparna Sridharan, Associates with inputs from and Rutuja Pol, Senior Associate and Anirudh Rastogi, Managing Partner at Ikigai Law.

Image Credits: pixabay

[1] Notification dated 13th July 2021, National Pharmaceuticals Pricing Authority, https://www.nppaindia.nic.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Notification-TMR-5-Medical-Devices.pdf.

[2] Paras 6 and 19, Drugs (Price Control) Order, 2013, http://www.nppaindia.nic.in/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/DPCO2013_03082016.pdf.

[3]See: Fuhr, T., George, K., Pai, J., The Business Case for Medical Device Quality, McKinsey Center for Government, (2013), https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/dotcom/client_service/public%20sector/regulatory%20excellence/the_business_case_for_medical_device_quality.ashx. at p. 5-7; Chilukuri, S., Gordon, M., Musso, C., Ramaswamy, S., Design to value in medical devices, McKinsey & Company, (2017), https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/dotcom/client_service/pharma%20and%20medical%20products/pmp%20new/pdfs/774172_design_to_value_in_medical_devices1.ashx, at. p. 6.

[4] Niti Aayog, Rationalization of Trade Margins in Medical Devices – A Consultation Paper, (June 08, 2018), https://www.niti.gov.in/writereaddata/files/document_publication/MedicalDevice-concept-note.pdf,

[5] Niti Aayog, Rationalization of Trade Margins in Medical Devices – A Consultation Paper, (June 08, 2018), https://www.niti.gov.in/writereaddata/files/document_publication/MedicalDevice-concept-note.pdf, at para 4.

[6] Rajiv Nath, Govt must consider trade margin rationalisation for medical devices import; Here’s why, (March 03, 2020), https://www.financialexpress.com/opinion/govt-must-consider-trade-margin-rationalisation-for-medical-devices-import-heres-why/1886936/.

[7] Niti Aayog, Rationalization of Trade Margins in Medical Devices – A Consultation Paper, (June 08, 2018), https://www.niti.gov.in/writereaddata/files/document_publication/MedicalDevice-concept-note.pdf, at para 5.

[8] Rajiv Nath, Trade margin rationalization, (November 06, 2018), https://www.dailypioneer.com/2018/columnists/trade-margin-rationalisation.html

[9] Rajiv Nath, Trade margin rationalization, (November 06, 2018), https://www.dailypioneer.com/2018/columnists/trade-margin-rationalisation.html

[10] India and US could agree on trade margin regulation for high-end medical devices, https://theprint.in/health/india-and-us-could-agree-on-trade-margin-regulation-for-high-end-medical-devices/364378/.

[11] APACMed, Asia Pacific Medical Technology Association (APACMed) Comments on “Rationalization of Trade Margins in Medical Devices – A Consultation Paper” dated 8 June 2018. (July 12, 2018), https://apacmed.org/content/uploads/2018/10/APACMed-Letter-Rationalization-of-Trade-Margins-in-Medical-Devices-07102018.pdf

[12] India and US could agree on trade margin regulation for high-end medical devices, https://theprint.in/health/india-and-us-could-agree-on-trade-margin-regulation-for-high-end-medical-devices/364378/.

[13] Pavan Choudhary, Trade margin rationalization will bring in transparency in pricing regulations of medical devices: MTaI, (July 29, 2021), https://www.financialexpress.com/lifestyle/health/trade-margin-rationalization-will-bring-in-predictability-and-transparency-in-pricing-regulations-mtai/2299369/.

[14] Competition Commission of India, Market study on the pharmaceutical sector: key findings and observations, (November 18, 2021), at pg. 42, para 78. (See: https://www.cci.gov.in/sites/default/files/whats_newdocument/Market-Study-on-the–Pharmaceutical–Sector-in-India.pdf)

[15] Competition Commission of India, Market study on the pharmaceutical sector: key findings and observations, (November 18, 2021), at pg. 42, para 78. (See: https://www.cci.gov.in/sites/default/files/whats_newdocument/Market-Study-on-the–Pharmaceutical–Sector-in-India.pdf)

[16] Para 7, Notification dated 13th July 2021, National Pharmaceuticals Pricing Authority, https://www.nppaindia.nic.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Notification-TMR-5-Medical-Devices.pdf.

[17] Shardul Nautiyal, Med Tech industry asks NPPA to rationalize trade margins for imported and indigenous medical devices, (July 17, 2021), https://www.financialexpress.com/lifestyle/health/med-tech-industry-asks-nppa-to-rationalize-trade-margins-for-imported-medical-devices-and-indigenous-medical-devices/2290984/.

[18] World Health Organization, WHO guideline on country pharmaceutical pricing policies, (January 01, 2015), https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240011878.

[19] World Health Organization, WHO guideline on country pharmaceutical pricing policies, (January 01, 2015), https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240011878.

[20] World Health Organization, WHO guideline on country pharmaceutical pricing policies, (January 01, 2015), https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240011878, at p. vii-viii.

[21] DLA Piper, Regulatory, Pricing and Reimbursement Overview, (May 27, 2020) https://pharmaboardroom.com/legal-articles/regulatory-pricing-and-reimbursement-overview-norway/