Initial phase of discourse

At the WTO’s first Ministerial Conference in Singapore in 1996, Members agreed to expand world trade in information technology (IT) products under the aegis of the WTO. To formalise this, a few Members signed the Information Technology Agreement (ITA) through the “Ministerial Declaration on Trade in Information Technology Products”.[1] Under the ITA, Members agreed to eliminate customs duties for a defined list of IT products which, among others, included computers, semiconductors, software, scientific instruments.[2] At the second Ministerial Conference in Geneva in 1998, recognising that global e-commerce is “creating new opportunities for trade”, Members adopted a declaration on global e-commerce. This declaration called upon the General Council to establish a comprehensive work programme on e-commerce (hereafter, WorkProgramme) to examine all trade-related issues concerning e-commerce.[3] In addition, Members agreed to continue the moratorium on imposing customs duties on electronic transmissions (hereafter, Moratorium) agreed under the ITA. The scope of the Work Programme was meant to be exploratory in nature, and its mandate did not allow Members to initiate negotiations for a potential e-commerce framework.

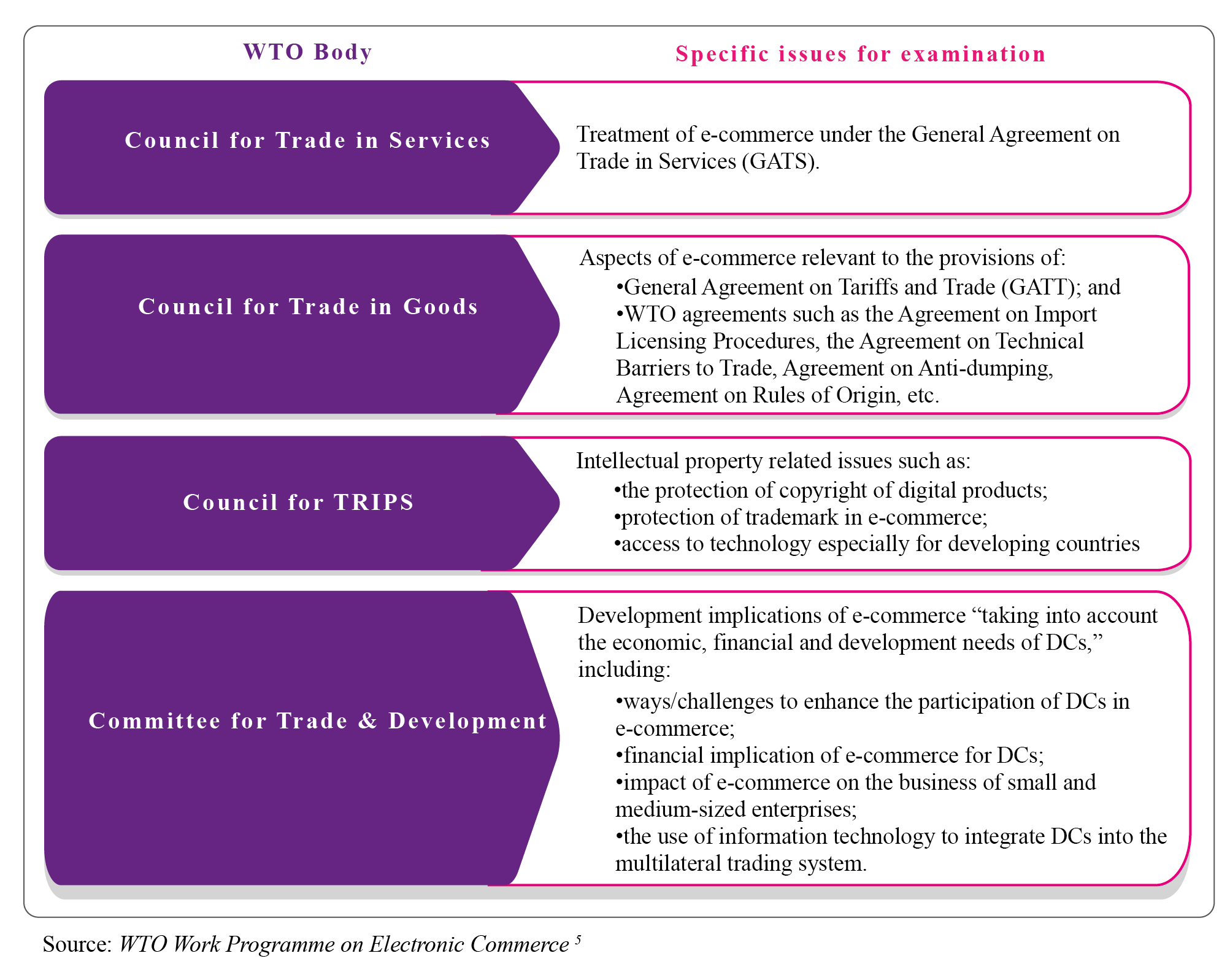

The Work Programme was adopted in September 1998 which allocated four WTO bodies to examine specific trade-related issues concerning e-commerce and the applicability of existing WTO agreements.[4] These were: the Council for Trade in Services; Council for Trade in Goods; Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS) and the Committee for Trade & Development. The issues to be examined by these four bodies were:

Source: WTO Work Programme on Electronic Commerce[5]

The overall work of these four bodies was reviewed by the General Council. Based on the progress reports submitted by the subsidiary bodies, the General Council had to submit its recommendations to Members for further action at each Ministerial Conference.[6] Over the next two years, the four bodies met regularly and submitted periodic progress reports to the General Council.[7]

Cross-cutting and procedural issues: Deadlock in the General Council

In addition to the work of the WTO bodies, the Work Programme allowed the General Council to examine any issue of a cross-cutting nature. In June 2001, at the General Council’s first dedicated discussion on e-commerce (hereafter, Dedicated Discussion), the General Council identified seven cross-cutting issues for deliberation by Members.[8] These were: (i) classification of digital products as “goods” or “services”; (ii) issues concerning developing and least-developed countries; (iii) revenue implications of e-commerce, especially for DCs; (iv) relationship between e-commerce and traditional forms of commerce to assess short-term disadvantages for DCs; (v) impact of continued moratorium on custom duties on DCs; (vi) competition related issues including constraints on e-commerce due to concentration of market power; and (vii) jurisdictional challenges for e-commerce disputes.[9] Of these, the two most important and hotly debated issues were: classification of digital products; and moratorium on custom duties.[10]

- Classification of digital products as “goods” or “services”: There was no consensus on whether to treat digital products as goods or services, especially for products available in electronic as well as physical form such as software, books, music, etc. If treated as goods, they fall under GATT which offers various protections including non-discriminatory treatment between similar domestic and foreign products. However, if treated as services, they fall under GATS under which Members are free to choose their commitments and there are no unconditional protections available. Therefore, a classification under GATT would imply lesser duty than a classification under GATS. Consequently, developed countries like US pressed for the treatment of digital content under GATT. However, a majority of Members including the EU opposed US’s position, arguing that GATS was more equipped to regulate digital trade.

- Extension of Moratorium on custom duties: Various DCs and least-developed countries (LDCs) were against a permanent Moratorium on customs duties due to potential tariff losses. However, most developed countries favoured its continuation pressing for free and open digital trade.

In a series of Dedicated Discussions held from 2001 to 2003, Members could not reach a consensus on these two cross-cutting issues. In addition, there was a deadlock on the procedural issue regarding a change in the mandate of the Work Programme. While some countries favoured the continuation of the Work Programme due to various unresolved issues, a few others favoured the creation of an additional body to discuss cross-cutting issues in a more formalised manner. These three issues paralysed discussions in the General Council.[11] Consequently, even the work in the four WTO bodies suffered and no progress was made until the tenth Ministerial Conference in Nairobi in 2015.[12] For instance, the Council for Trade in Goods reported to the General Council that given the unresolved issues, work in the Council could not go any further.[13] Similarly, the discussions on issues of e-commerce were completely absent from meetings of the Council for TRIPS from 2003 to 2016.[14]

Meanwhile, the Work Programme came to be considered in the Ministerial Conferences in Doha (2001), Hong Kong (2005), Geneva (2009), Geneva (2011) and Bali (2013). However, due to a paralysis in the work of the WTO bodies and a deadlock in the General Council, no issues came to be discussed. The Members kept renewing the mandate of the Work Programme with a hope that the exploratory work will continue.[15]

New and invigorated phase of discourse

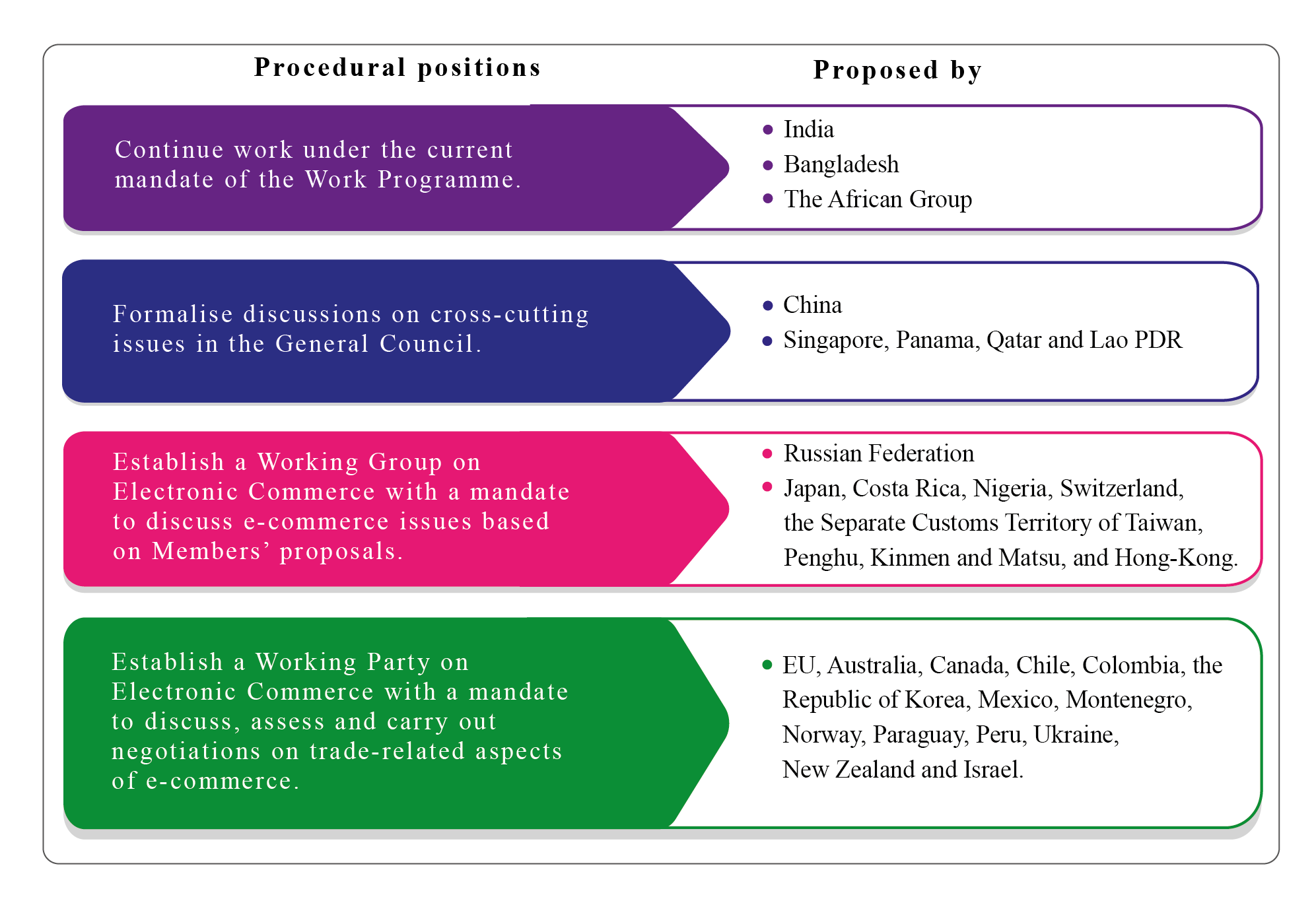

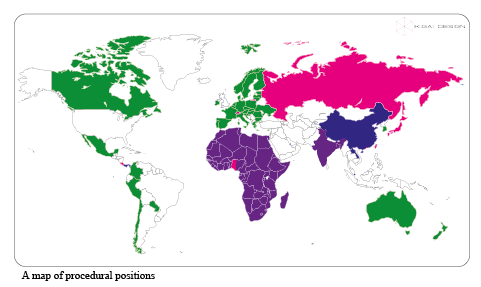

At the tenth Ministerial Conference in Nairobi, Members decided to reinvigorate work under the Work Programme until the next session in 2017.[16] In the lead up to the eleventh Ministerial Conference (MC11) in Buenos Aires in 2017, the work undertaken by the Members intensified, with 8 proposals tabled by the General Council for discussion at the Ministerial Conference.[17] These proposals focussed on the procedural issue of changing the mandate of the Work Programme. The positions of Members were:

Many DCs and LDCs, including India and South Africa, were in favour of continuing the current mandate of the Work Programme and opposed any future negotiations on e-commerce.[18] Even the African Group categorically opposed any change to the current structure or institutional arrangement of the Work Programme.[19] This was mainly because of various cross-cutting issues which needed further discussion and resolution, without which negotiations on e-commerce rules would be premature.[20] China supported the continuation of the Work Programme, however, it proposed a more serious discussion on cross-cutting issues in the General Council.[21] It did not, however, comment on any potential negotiations on e-commerce. Countries like Switzerland, Hong-Kong, Japan proposed the establishment of a working group which could assess, based on Members’ proposals, issues such as the priority needs of DCs and LDCs, challenges for micro, small and medium-sized enterprises, etc.[22] This working group would report on its progress to the General Council which would make further recommendations for action.[23] The reason behind proposing a working group was to have one body to assess important issues instead of four different bodies undertaking exploratory work. Finally, a few countries including developed countries like Australia, the EU and Canada pressed for a working party on e-commerce which would carry out negotiations on e-commerce.[24]

At MC11, due to a lack of consensus among the Members, a decision was taken to continue the existing mandate of the Work Programme. However, 71 Members issued a Joint Statement expressing their decision to initiate exploratory work towards future WTO negotiations on e-commerce.[25] This plurilateral initiative was spearheaded by Japan, Australia, the EU and the United States after their failure to secure multilateral consensus on the proposal to establish a working party on e-commerce.[26] Developed countries were eager to accelerate e-commerce discussions and initiate negotiations to benefit from digital trade. However, many developing countries like India, Indonesia and the African nations held their earlier ground and refused to join the plurilateral initiative.

Throughout 2018, the Joint Statement group held nine meetings to discuss proposals submitted by Members on various issues. These issues were: moratorium on customs duties; privacy protection; online security; data localization norms; interests of DCs and LDCs; inclusion and protection of MSMEs; infrastructure for electronic trade in DCs, among others.[27] Concluding these exploratory discussions, 76 Members released another Joint Statement at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2019 announcing their intention to initiate e-commerce negotiations.[28] India opposed this move on three grounds: a lack of mandate under the WTO to initiate negotiations, unpreparedness by countries and several unresolved substantive policy issues.[29] Despite strong opposition from major DCs, a total of 83 Members participated in six negotiating rounds in 2019.[30] Various Members have submitted their proposals and discussions papers. The key takeaways from the proposals of some countries are set out below:

- United States: The US submitted a discussion paper on e-commerce calling for “highest standard in safeguarding and promoting digital trade”. The paper builds on the commitments contained in the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the U.S-Mexico-Canada Agreement, and calls for unrestricted cross-border data flow and fair treatment of digital products, amongst other issues.[31]

- European Union: EU submitted a text proposal. However, unlike the US proposal, EUs proposal allows Members to adopt safeguards appropriate to ensure protection of personal data and privacy.[32]

- China: While US and EU’s proposals do not mention issues related to DCs and LDCs, China’s proposal calls for a focus on the challenges faced by these countries. China’s proposal also calls for respect for Members’ policy objectives on internet sovereignty, data security and privacy protection.[33]

- Côte d’Ivoire: Côte d’Ivoire’s proposal focusses on the technological challenges facing low-income DCs and LDCs and the importance of ensuring their participation in the ongoing plurilateral negotiations.[34]

The road ahead

In December 2019, the General Council decided to “reinvigorate” the work under the Work Programme and called for structured discussions in early 2020, especially on cross-cutting issues.[35] It appears that two parallel discourses are taking place on e-commerce – (i) multilateral discussions on the Work Programme in the General Council; and (ii) plurilateral negotiations in relation to the Joint Statement. While Members of both groups were hoping to make progress at the Twelfth Ministerial Conference in Kazakhstan in June, 2020, the Conference has been cancelled in light of the COVID-19 outbreak.[36] Until further negotiations can restart, Members should rethink the practicality and fruitfulness of parallel discussions on e-commerce at the WTO, especially after a slow-moving journey of over two decades.

This piece has been authored by Kruthi Venkatesh, a consultant working with Ikigai Law, with inputs from Nehaa Chaudhari, Director (Public Policy), Ikigai Law.

[1] World Trade Organisation, Ministerial Declaration on Trade in Information Technology Products, Ministerial Conference WT/MIN(96)/16 (13th Dec., 1996), available at, https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/itadec_e.pdf (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[2] Id., at 17.

[3] World Trade Organisation, Ministerial Conference, Declaration on Global Electronic Commerce, Second Session WT/MIN(98)/DEC/2 (25th May, 1998), available at, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009-DP.aspx?language=E&CatalogueIdList=4814,34856,20308&CurrentCatalogueIdIndex=1&FullTextHash= (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[4] World Trade Organisation, Work Programme on Electronic Commerce, WT/L/274 (30th Sep., 1998), available at, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009-DP.aspx?language=E&CatalogueIdList=22421,14657,30467,30446,27847,31348,4101,17078,19349,3664&CurrentCatalogueIdIndex=5&FullTextHash=371857150&HasEnglishRecord=True&HasFrenchRecord=True&HasSpanishRecord=True (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[5] Id., para. 2-5.

[6] Id., para 1.2.

[7] See World Trade Organisation, Interim Report to the General Council, GATS Council S/C/8 (31st Mar., 1999); World Trade Organisation, Communication from the Chairman of the CTD, General Council, WT/C/23 (9th Apr., 1999); World Trade Organisation, Communication from the GATT Council Chairman, General Council WT/GC/24 (12 Apr. 1999); World Trade Organisation, Progress Report to the General Council, TRIPS Council IP/C/18 (30th July., 1999).

[8] World Trade Organisation, Dedicated Discussion on Electronic Commerce, General Council, WT/GC/436, 6th July, 2001, available at, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/WT/GC/W436.pdf (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[9] Id.

[10] See Sacha Wunsch-Vincent, WTO, E-Commerce and Information Technologies: From the Uruguay Round through the Doha Development Agenda, Report for the United Nations Information and Communication Technologies Task Force, pg. 15, April, 2005, available at, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/serv_e/sym_april05_e/wunschvincent_e.pdf (hereafter Sacha Wunsch-Vincent, WTO, E-Commerce and Information Technologies) (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[11] Sacha Wunsch-Vincent, WTO, E-Commerce and Information Technologies, supra note 10, at 10.

[12] Yasmin Ismail, E-commerce in the World Trade Organization: History and latest developments in the negotiations under the Joint Statement, International Institute for Sustainable Development, at 10, (Jan., 2020), available at, https://www.iisd.org/sites/default/files/publications/e-commerce-world-trade-organization-.pdf (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[13] See Council for Trade in Goods, Report to the General Council on the Work Programme on Electronic Commerce, G/L/635, para 2 (9th July, 2003), available at, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009-DP.aspx?language=E&CatalogueIdList=96554,17152,18152,31670&CurrentCatalogueIdIndex=1&FullTextHash=&HasEnglishRecord=True&HasFrenchRecord=True&HasSpanishRecord=True (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[14] See ICTSC, E-Commerce Returns to WTO TRIPS Council Agenda, Bridges News, 16th June, 2016, available at, https://www.ictsd.org/bridges-news/bridges/news/e-commerce-returns-to-wto-trips-council-agenda (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[15] See World Trade Organizations, Ministerial Conferences, available at, https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/minist_e/minist_e.htm (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[16] World Trade Organization, Work Programme on Electronic Conference, Ministerial Decision of 19 December 2015, Ministerial Conference, Tenth Sess. WT/MIN(15)/42 – WT/L/977, (21st Dec., 2015), available at, https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/minist_e/mc10_e/l977_e.htm (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[17] See General Council, Work Programme on Electronic Commerce, Report by the Chairman, WT/GC/W/739, at 1.6 (1st Dec., 2017), available at, https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:f-UWpbmkO6kJ:https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx%3Ffilename%3Dq:/WT/GC/W739.pdf+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=in (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[18] Bhattacharya, D, M Rahman and A.M. Suchi, Post-MC11 Trade Agenda for the Least Developed Countries, International Trade Working Paper 2018/05, Commonwealth Secretariat, at 10 (2018), available at, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/ef4773c8- en.pdf?expires=1590984341&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=EE23D62016FB46371D127E9B1734263D (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[19] World Trade Organisation, Work Programme on Electronic Commerce, Statement by the African Group, WT/MIN(17)/21 (6th Dec., 2017), available at, https://www.tralac.org/images/Resources/MC11/mc11-work-programme-on-electronic-commerce-statement-by-the-african-group-6-december-2017.pdf (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[20] Id.

[21] World Trade Organisation, Work Programme on Electronic Commerce, Communication from China, WT/MIN(17)/34 (9th Dec., 2017).

[22] World Trade Organisation, Work Programme on Electronic Commerce, Communication from Japan, Costa Rica, Nigeria, Switzerland, the Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu, and Hong-Kong, WT/MIN(17)/26 (8th Dec., 2017).

[23] Id.

[24] World Trade Organisation, Work Programme on Electronic Commerce, Communication from EU, Australia, Canada, Chile, Colombia, the Republic of Korea, Mexico, Montenegro, Norway, Paraguay, Peru, The Republic of Moldova, The Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Ukraine, New Zealand and Israel, WT/MIN(17)/15/Rev.1 (8th Dec., 2017).

[25] World Trade Organisation, Joint Statement on Electronic Commerce, WT/MIN(17)/60 (13th Dec., 2017), available at, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009-DP.aspx?language=E&CatalogueIdList=250607,240871&CurrentCatalogueIdIndex=1&FullTextHash=371857150&HasEnglishRecord=True&HasFrenchRecord=True&HasSpanishRecord=True (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[26] Third World Network, North and its Allies in South opt for Plurilateral on E-Com and MSMEs, (15th Dec., 2017), available at, https://www.twn.my/title2/wto.info/2017/ti171232.htm (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[27] Katya Garcia-Israel and Julien Grollier, Electronic Commerce Joint Statement: Issues in the Discussion Phase, CUTS International, at 4 (Oct., 2019), available at, http://www.cuts-geneva.org/pdf/1906-Note-RRN-E-Commerce%20Joint%20Statement1.pdf (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[28] World Trade Organisation, Joint Statement on Electronic Commerce, WT/L/1056, (25th Jan., 2019), available at, https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2019/january/tradoc_157643.pdf (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[29] UNCTAD, Countries discuss proposed WTO talks to boost e-commerce, 5th April, 2019, available at, https://unctad.org/en/pages/newsdetails.aspx?OriginalVersionID=2051 (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[30] See Katya Garcia-Israel and Julien Grollier, Electronic Commerce Joint Statement: Issues in the Negotiations Phase, CUTS International, at 16 (Oct., 2019), available at, http://www.cuts-geneva.org/pdf/1906-Note-RRN-E-Commerce%20Joint%20Statement2.pdf (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[31] World Trade Organization, Joint Statement on Electronic Commerce Initiative, Communication from the United States, INF/ECOM/5, (25th Mar., 2019), available at, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/DDFDocuments/252610/q/INF/ECOM/5.pdf (last accessed on 3rd May, 2020).

[32] World Trade Organization, Joint Statement on Electronic Commerce, EU Proposal for WTO Disciplines and Commitments Relating to Electronic Commerce, INF/ECOM/22 (26th Apr., 2019), available at, http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2019/may/tradoc_157880.pdf (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[33] World Trade Organization, Joint Statement on Electronic Commerce, Communication from China, INF/ECOM/19 (24th Apr., 2019), available at, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/DDFDocuments/253560/q/INF/ECOM/19.pdf (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[34] World Trade Organization, Joint Statement on Electronic Commerce, Communication from Côte d’Ivoire, INF/ECOM/49 (16th Dec., 2019), available at, https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:QrDwBQIXzysJ:https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx%3Ffilename%3Dq:/INF/ECOM/49.pdf+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=in (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[35] World Trade Organization, Work Programme on Electronic Commerce, WT/L/1079 (11th Dec., 2019), available at, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009-DP.aspx?language=E&CatalogueIdList=259703,259704,259705,259706,259710,259651,259652,259663,259304,259264&CurrentCatalogueIdIndex=5&FullTextHash=&HasEnglishRecord=True&HasFrenchRecord=True&HasSpanishRecord=True (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).

[36] World Trade Organisation, Ministerial Conferences, available at, https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/minist_e/mc12_e/mc12_e.htm (last accessed on 30th May, 2020).