The nearly two-year long challenge by Indian cryptocurrency users, traders and exchanges, against the April 6, 2018 RBI circular[1], which cut off such users’ access to the formal economy has come to a close. On Tuesday, 28 January 2020 arguments in the writ petition challenging the circular before the Supreme Court were concluded and the judgment was delivered on 4 March 2020.

Ikigai Law filed the first petition before the Supreme Court in this matter on behalf of exchanges Koinex, CoinDCX, Throughbit and CoinDelta. A copy of the petition filed by Ikigai Law can be accessed here (part 1, part 2 & part 3). The firm worked with Senior Advocate Nakul Dewan and AoR Avinash Menon.

We have created a short summary of arguments made by both sides.

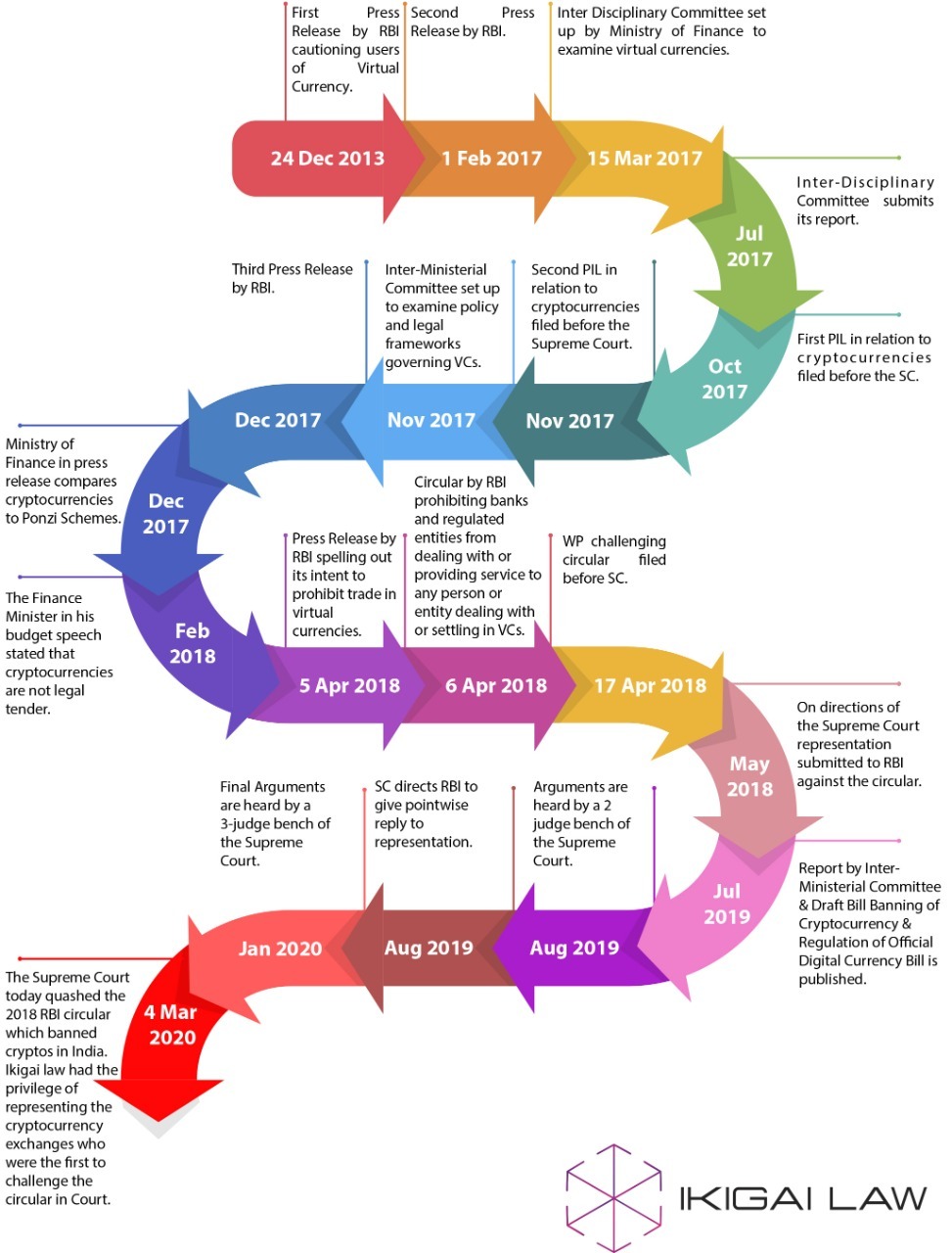

To put things in context, we begin with a brief timeline of events in India that affected the regulation of cryptocurrencies (or digital assets or crypto assets, as we prefer to call them).

This is followed by:

A. Summary of submissions made by the Petitioners. These include submissions:

1. on the legal character of virtual currencies;

2. to show that the circular violates the rights of the Petitioners under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution to carry on their occupation, trade or business;

3. to show that the RBI has acted beyond the scope of its powers;

4. to show that the RBI has acted arbitrarily;

5. to show that the RBI acted in a pre-determined manner and jumped the gun in virtually outlawing virtual currencies;

6. contrasting how virtual currencies are regulated across jurisdictions, and

7. how virtual currencies may be used to fight crime.

B. Summary of arguments made by RBI;

C. Summary of reply to the arguments made by RBI.

A Brief Timeline

A. Summary of Arguments by the Petitioner

1. On the legal character of virtual currencies

1.1 Virtual currency/cryptocurrency is not Money–

i. Money functions as a unit of account, store of value, a medium of exchange and final discharge of debt.

ii. Almost anything can be reduced in terms of money and then traded for goods and services of equivalent value. In this manner, almost anything can act as a unit of account and store of value.

iii. However, to function as a “medium of exchange” a certain degree of acceptance by the society of required. People must have enough faith in the value of money to exchange goods and services for money. This is the social function of money. Virtual Currencies have not achieved that degree of acceptance to become a socially acceptable medium of exchange.

iv. Neither can virtual currencies be used to legally discharge a debt. If you seek to settle a debt and want to pay off your debtor in cash (i.e. currency notes), the debtor has to agree. If you seek to pay your debtor in virtual currencies, then the debtor has a choice to accept or reject your offer.

1.2 Certain characteristics of virtual currency resemble those of a “good”.

1.3 Counsel for Petitioners cited a report prepared by the UK Jurisdictional Taskforce that examines certain legal issues pertaining to crypto assets and smart contracts[2]. The report characterises virtual currencies as “property” as they–

i. Are definable- A virtual currency is represented by two sets of data parameters- public and private. The public parameter contains information regarding the ownership, value and transactional history of the asset and is sufficient to define the asset.

ii. Can be exclusively controlled- The private parameter permits transfer and other dealings of the crypto asset. Knowledge of the private key confers control of the crypto asset to the exclusion of others.

iii. Permanent- Crypto assets are as permanent as other conventional financial assets.

iv. Stable- Despite certain risks, the taskforce was of the opinion that crypto assets are stable.

1.4 He also cited how courts in the US and Singapore have treated virtual currencies[3].

2. The circular violates the rights of the Petitioners under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution to carry on their occupation, trade or business.

2.1 Virtual currency exchanges cannot carry out their business without access to banking channels.

i. A virtual currency exchange is an intermediary that connects a buyer and a seller.

ii. It collects commission for each transaction vide digital payments. It needs access to banking channels to function.

iii. Even as a simple business it has operating expenses such as rent, salary, payment to vendors, etc., for all of which it needs access to banking channels.

iv. Cutting of the access for virtual currency exchanges from formal banking channels is akin to civil death for such exchanges.

2.2 The circular has restricted the ability of the Petitioners to access their own money for the purpose of a trade which is legal.

3. RBI has acted beyond the scope of its powers

3.1 The issuance of the circular by RBI was ultra vires. It is a colourable exercise of power as the RBI was apparently issuing directions only to entities that it had power over (i.e. banks and payment systems), however, has affected individuals and entity over which the RBI does not have any jurisdiction (i.e. users, holders and traders of virtual currencies)[4].

3.2 There is no legislative ban on virtual currencies. If the legislature has not banned virtual currencies, then the RBI as a delegate of the legislature cannot do so. It has acted beyond its remit.

3.3 The circular is the first instance when the RBI has issued its power to indirectly prohibit the trade of any good.

3.4 The concerns expressed in the press releases are directed towards “the users, holders and traders” of virtual currency i.e. consumers of virtual currencies. These are essentially means for consumer awareness. The RBI, as the apex regulator of monetary and fiscal policy in India, should not be concerned with consumer welfare. If RBI does want to protect consumers then it should be only in their capacity as depositors.

3.5 Similarly, there are separate agencies departments to counter-terrorism. The use of virtual currencies for funding terror is the concern of the counter-terrorism agencies and not the RBI. The consumption of excessive electricity in mining virtual currencies is again not the concern of the RBI.

3.6 Although, the Banking Regulation Act, 1949; the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 and Payment and Settlement System Act, 1934 give the RBI wide powers, to take such regulatory action as it deems necessary in public interest, this does not amount to unfettered discretion. A statute must be read in its context.

4. RBI has acted arbitrarily

4.1 RBI has irrationally deviated from its cautionary stance taken at the time of issuance of the first circular even though there was no change in the underlying facts and circumstances.

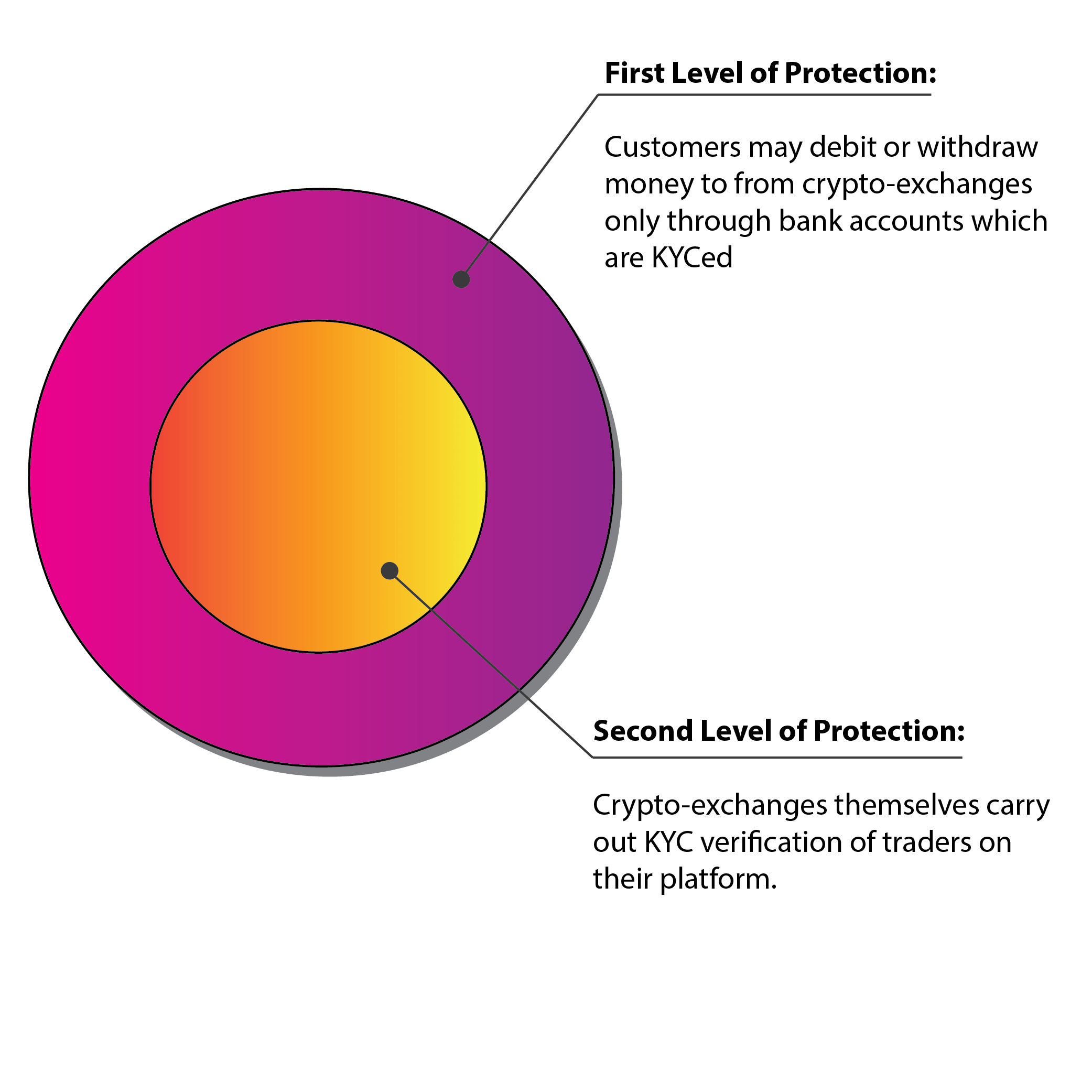

4.2 The circular rather than addressing the concerns/risks expressed (i.e. can be used for illegal illicit activities, no customer redressal mechanism etc.) in the preceding press-releases has only escalated them. Because of the circular many crypto-exchanges have been shut down. These exchanges had put in place KYC and AML mechanisms. Such mechanisms would allow law enforcement authorities to trace cryptocurrency transactions and also allowed for some form of consumer redressal as the crypto-exchanges would have mediated the transactions.

4.3 The counsel for the Petitioners, explained this point by giving the analogy of two concentric circles. If trade in virtual currencies occurred through crypto-exchanges, there would be two levels of checks on each transaction. Firstly, users would only be able to enter into a transaction by debiting or withdrawing money through their bank accounts (which would be KYC compliant). Secondly, the exchanges themselves carry out KYC and implement AML practices. The circular unravels this safety net, to a large extent, by cutting-off banks from the ecosystem.

4.4 The circular does not ban crypto-trade but only bars banks and other entities regulated by RBI from providing any services to users, traders and holders engaging in virtual currency dealings. This means that crypto-trade may still be carries on in India, just not through banks. All crypto-trade has thus been relegated to the informal economy which amplifies the risks stated in the press releases, rather than arresting them.

4.5 The RBI circular against virtual currency was not a proportionate response to the risks associated with virtual currencies.

4.6 The RBI had no empirical data before it through which it could draw the conclusion that virtual currencies were a possible threat to the payment or credit system of the country.

4.7 Virtual currencies have varying characteristics (unidirectional, bi-directional, anonymised, pseudo anonymised etc). Each virtual currency will have a separate set of concerns. The RBI circular takes out all virtual currencies irrespective of whether the risks outlined in the press releases apply to them or not.

5. RBI jumped the gun

5.1 The RBI had without any material basis made up its mind to ban virtual currencies.

5.2 The RBI’s pre-determined approach was evident through its conduct. In the deliberations of the inter-ministerial committee on 04.04.2018 (i.e. 2 days before the circular) when several government agencies were deliberating on best way to deal regulate virtual currencies, the governor of RBI at once interjected and expressed his view that virtual currencies should be banned. Notably, other regulators including DEA (Department of Economic Affairs- an agency which is responsible for preventing funding of terrorism activities) felt that regulating virtual currencies is better approach than a ban. Even SEBI (who would be more concerned with the speculative nature of virtual currencies), at this point was in favour of regulation than a ban. Two days letter RBI imposed its opinion on the public at large by implementing the circular. RBI has thus deliberately acted in an arbitrary manner with little to no regard of the rights of virtual currency users. This is an instance of “malice in law[5]”.

5.3 All regulators had agreed that if a ban on virtual currency was to be put in place, the first step would be the legislature out-lawing virtual currency through an act of parliament. However, the RBI acting on its own pre-determined agenda, proceeded to ban virtual currencies by the only means available to it, i.e. by prohibiting its regulated entities from facilitating anyone dealing in virtual currencies.

6. Regulation of virtual currencies in other jurisdictions

6.1 Different jurisdictions have adopted different approaches for regulating virtual currencies.

6.2 Most developed economies including several G20 countries have chosen to regulate rather than prohibit them.

6.3 Countries that have on the other hand chosen to prohibit cryptocurrencies, are those which have a different set of constitutional values as opposed to ours.

7. How Virtual Currencies can be used to fight crime

Virtual Currencies have long been vilified because of the incorrect notion that they aid criminals in anonymously transmitting funds across the world. This is incorrect. Investigators have in fact successfully used virtual currencies to track criminals and prosecute crimes. For instance, the IRS traced and de-anonymised transactions done in virtual currencies to take down the largest dark web child pornography website in the world. [6]

B. Summary of submissions by RBI

1. The RBI has ample power and authority under the Banking Regulation Act, 1949; the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 and the Payment and Settlement Systems Act to issue the circular.

2. There was more than enough material available before the RBI, domestic and international, for it to be satisfied that it was necessary to issue the circular.

3. The issuance of the circular was a calibrated and proportionate response to the dangers posed by virtual currencies. It did not happen over-night. The RBI had been warning consumers since 2013 of the dangers of virtual currencies. If they chose to indulge in trading virtual currencies despite these risks, then they did so at their own risk and consequences.

4. In matters of economic and fiscal policy, policy enunciated by RBI has the statutory force of law, and courts should not lightly interfere with discretion exercised by the executive after due deliberation.

5. Virtual currencies are a new complex creature to which regulators around the world are responding to. The responses vary. The RBI is keeping a close watch on all developments.

6. All options for regulating virtual currencies were considered by the expert committee. There has been a consideration at every level.

7. RBI sees it as its paramount duty to protect the payment system of the country. If there is even a remote possibility that the payment system will be compromised, then the RBI may take all steps necessary to nip this danger in the bud.

8. Virtual currencies were being used in a manner akin to legal currency. Microsoft, Wikipedia accepted payments in bitcoins. Purse allowed users to purchase products from Amazon using bitcoins.

9. Virtual currencies allowed a parallel ecosystem to develop for remittance of money abroad without the oversight of regulators.

10. RBI took the court through extensive literature on virtual currency which it had allegedly relied on for reaching its decisions.

11. While during the deliberations of the Inter-Ministerial Committee there may have been a difference of opinion, the final unanimous recommendation of the committee was to ban virtual currencies.

C. Summary of arguments in reply to RBI’s submissions

1. Purpose of asking the regulator to show satisfaction is to get rid of caprice. There is no defence for a capricious or arbitrary act.

2. The regulator, when demonstrating that it has adequately deliberated an issue at hand (in this case, the potential and ill-effects of cryptocurrencies), it should be allowed to place reliance only on the documents it had actually relied on at the time of making the decision. If after a decision has been made, the Regulator is allowed to go and hunt for documents which may support its decision, then this would allow the regulator to act capriciously.

3. Even in matter of delegated legislation, while the courts should not examine the merits of the decision which was taken, they can and should examine the process by which the decisions was arrived at, including- was there enough material on record to arrive at the decisions; were other alternative measures considered, etc.

4. Technology is both a tool and a weapon depending on how it is used. Emails in their initial avatar were used exclusively by the US military. It was clear to all that if emails are allowed to be used widely, they could make the entire postal and telegraph infrastructure redundant. Had regulators in light of such legitimate fears prohibited or restricted the use of emails we would be living in very different times. What we fear today may become essential for us tomorrow. RBI has acted in fear seeing only the drawbacks of cyrptocurrencies and ignoring its potential.

Disclaimer: Ikigai Law were counsels to the four crypto-exchanges (Koinex, CoinDXC, CoinDelta and Throughbit) and certain traders in this matter.

Update 1 (28.02.2020): While the arguments are closed in the crypto writ petitions and the matter is reserved for orders, the learned Senior Counsel briefed by Ikigai Law, mentioned the petitions before the Supreme Court this Friday (28.02.2020) to update the court on judgments pronounced by the Court of Appeal in Singapore and High Court of Justice Business & Property Courts of England & Wales. The two judgments supported the statements made by the Counsel, that crypto currencies are akin to property.

The judgment of the Court of Appeal of Singapore in Quoine Pte Ltd v. B2C2 Ltd. [2020] SCGA(I) 02 (Relevant paras 137-144) can be viewed here, and the judgment of the High Court of Justice Business & Property Courts of England & Wales Commercial Court in AA v. Persons unknown who demanded bitcoins on 10th and 11th October 2019 and Ors [2019] EWHC 3556 (Comm) (relevant paras 55-61) can be viewed here.

Update 2 (4.03.2020): The Supreme Court has quashed the RBI circular imposing the banking ban on cryptocurrencies. It has also directed the unfreezing of bank accounts of the crypto-exchanges and refund of monies with interest. A summary of the judgment is available here.

References

[1] https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=11243&Mode=0

[2] Available at https://35z8e83m1ih83drye280o9d1-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/6.6056_JO_Cryptocurrencies_Statement_FINAL_WEB_111119-1.pdf

[3] B2C2 Ltd. v. Quoine Pte Ltd., [2019] 4 SLR 1; US v. Anthony R. Murgio, 209 F. Supp. 3d 698 (2016); US v. Faiella, 39 F. Supp. 3d 544 (S.D.N.Y. 2014); SEC v. Shavers, Case No. 4:13-Cv416 (E.D. Tex. Aug. 6, 2013; CFTC v. My Big Coin Pay Inc. (United States District Court, District of Massachusetts Civil Action No. 18-10077-Rwz); CFTC v. McDonnell (United States District Court Eastern District of New York Memorandum & Order 18-Cv-361)

[4] (1985)3 SCC 1

[5] (2010)9 SCC 437

[6] https://www.forbes.com/sites/kellyphillipserb/2019/10/16/irs-followed-bitcoin-transactions-resulting-in-takedown-of-the-largest-child-exploitation-site-on-the-web/#568b39ff1ed0