The classification debate: ‘goods’ or ‘services’

The Work Programme defines e-commerce as “the production, distribution, marketing sale or delivery of goods and services by electronic means”.[6] While the scope of e-commerce was clear, Members could not decide whether to treat digital products as ‘goods’ or ‘services’. Whether digital products are treated as goods or services will determine whether they fall under General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) which regulates trade in goods, or under General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) which regulates trade in services.

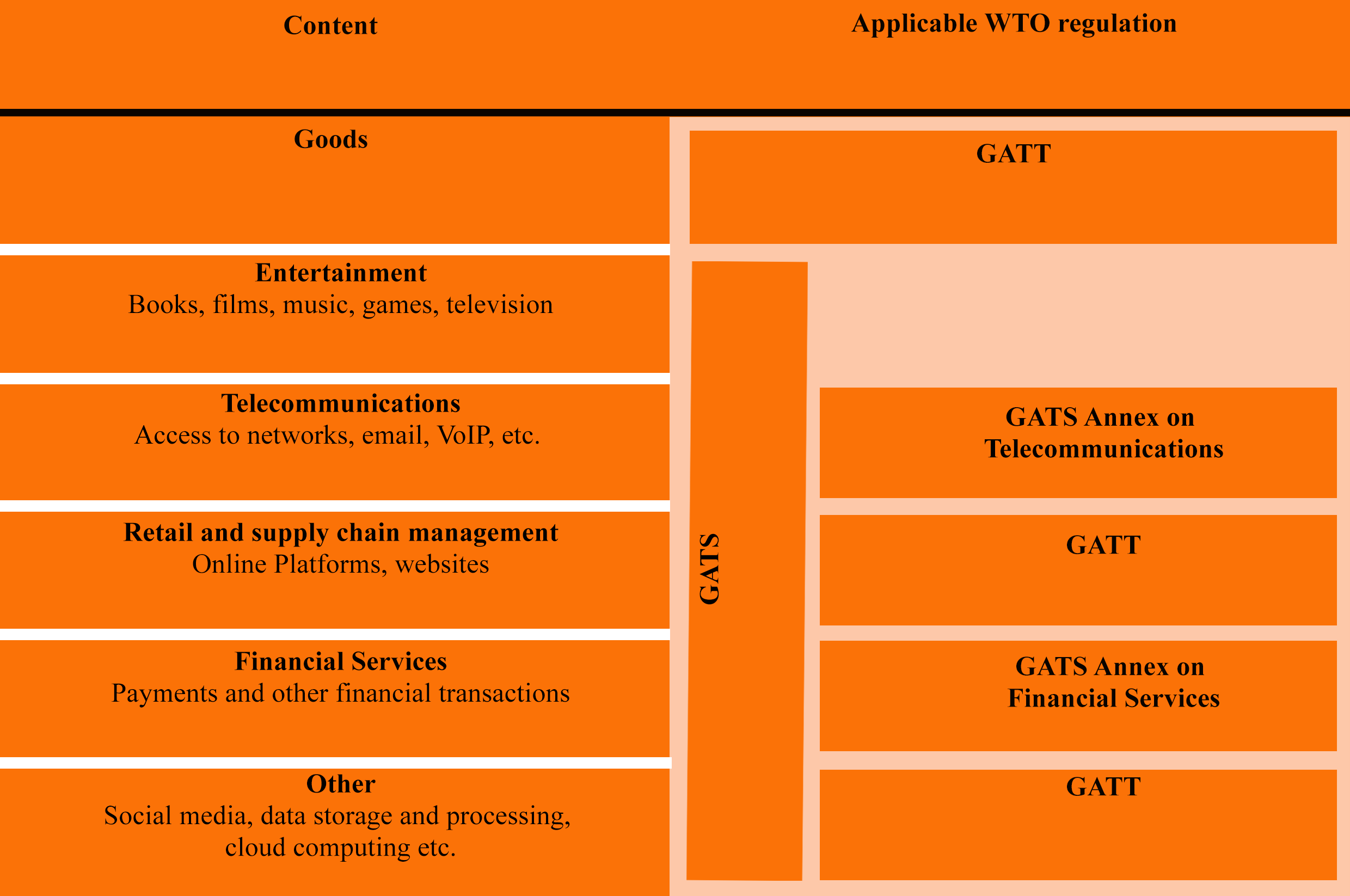

The uncertainty arose mainly with regard to the classification of those products which can be delivered in electronic form or on a physical carrier.[7] For instance, music cassettes, printed books, DVDs are also available as audio file/music streaming, e-books and movie streaming services, thereby blurring the distinction between goods and services.[8] Even software can be downloaded online or physically delivered. This creates an overlap, with the product in its physical form falling under GATT and in its digital form falling under GATS. The table below explains the overlap in the regulatory framework:

Source: López González, J. and J. Ferencz.[9]

For these digital products where there is an overlap between GATT and GATS, some countries favored the application of GATT, while others favored the application of GATS. This was mainly due to the different level of commitments and protections offered under GATT and GATS.

GATT v. GATS

The GATT framework is known for two core principles: (i) National Treatment i.e., non-discrimination between domestic and foreign ‘like’ products; and (ii) Most-Favored Nation (MFN) treatment i.e., benefits provided to the products of one country should be given to the products of every other country.[10] GATT also provides other protections such as reduced tariff. However, under GATS, these core principles of trade liberalization are not mandatory. Members are allowed to make exemptions to MFN treatment. Further, National Treatment is not unconditional and is applied only when a Member makes a commitment to provide national treatment to service in a particular sector.[11] Even other protections that exist under GATT are not available under GATS. Therefore, a classification under GATT would imply lesser duty and an unconditional applicability of the core principles, unlike a classification under GATS.

It is, therefore, no surprise that the United States (US) has been advocating a more liberal treatment of digital content under GATT. In its proposal to the General Council, the US argued that “[G]iven the broader reach of WTO disciplines accorded by the GATT (i.e. market access and national treatment are not dependent on specific commitments) there may be an advantage to a GATT versus GATS approach to such products”.[12] This position didn’t find much support in the WTO and was only advocated by Japan.[13] Contrary to this, the EU advocated for the application of GATS to digital products delivered electronically, and the application of GATT only to products delivered physically, even if ordered electronically.[14] This position was supported by many WTO Members for a variety of reasons: (1) Members argued that GATT had not been designed to include digital products. GATT was built on the basis of the Harmonized System, an international product nomenclature under which each product is given a code and arranged in a structure, to uniformly classify international trade in goods.[15] This Harmonized System only provides a nomenclature for products with physical identifications or characteristics and therefore, it could never regulate or place tariffs on digital products;[16] (2) GATS was already being applied to electronic delivery of services including a few digital products like downloadable movies and hence, it made sense to regulate all such transactions under GATS;[17] (3) Moreover, due to the flexibility under GATS to place restrictions on digital trade, Members could impose restraints on the global strength of US e-commerce companies.[18]

However, a few other WTO Members raised the issue that there cannot be a discrimination between digital products and their physical analogues, since a product delivered physically may enjoy national treatment, however its digital analogue may not.[19] As a solution, Indonesia and Singapore proposed that regardless of classification, MFN and National Treatment should be applied to all digital products to ensure fair, open and transparent market access for e-commerce.[20] However, Members could not reach a consensus and the issue of classification was left unresolved. Despite the initiation of the plurilateral negotiations on e-commerce in 2019,[21] the classification debate is still on-going at the WTO and continues to remain a contentious issue.

Moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions

In the Information Technology Agreement (ITA) signed by Members at the WTO’s first Ministerial Conference in Singapore in 1996, Members agreed to eliminate customs duties for a defined list of information technology products.[22] Thereafter, when the Work Programme was adopted in 1998, WTO Members agreed to continue the moratorium on custom duties on electronic transmissions (hereafter, Moratorium) temporarily, to allow e-commerce to grow.[23] Since then, the Moratorium was extended by the Members at every Ministerial Conference, with the recent extension, announced by the General Council in December 2019, until the Twelfth Ministerial Conference.[24] According to a study by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD),[25] the Moratorium results in a much higher revenue loss for developing countries – almost 92%, compared to developed countries with only 8% revenue loss. Expectedly, this has been one of the most intensely debated issues in the WTO’s e-commerce discussions.

Most developed countries in the e-commerce discussions favored the Moratorium, while many developing countries opposed it on grounds of revenue loss. The US, for instance, argued that the Moratorium should be made permanent and binding.[26] A few other developing countries sought time to understand the potential economic impact of the Moratorium on their countries, before they could comment on its permanency. Apart from the issue of revenue loss, two other issues complicated the debate further:

(i) ‘Carrier’ or ‘content’: There was no clarity on whether the Moratorium included only the ‘carrier’ of a digital product, that is, the transport service (physical or electronic) or if it also included the content, namely the digital product (e.g. software) or services (e.g. legal services).[27] However, this issue is closely connected to the classification debate as to whether digital ‘content’ is goods or services. If they are treated as goods, then customs duties can be imposed on them along with GATT principles of MFN and National Treatment.[28] But if they are treated as services, then Members will have the flexibility of choosing commitments under GATS.[29] Since both issues have been connected, the stalemate on the classification debate has affected a few aspects of the debate on Moratorium as well.

(ii) Technological neutrality: The Moratorium was inconsistent with the principle of ‘technological neutrality’ followed under GATS i.e., commitments such as National Treatment under GATS apply irrespective of the technological means used for the supply, thereby including electronic means. This implies that the products delivered physically could be subjected to customs duties, whereas products delivered electronically would be duty-free due to Moratorium being applicable on electronic transmissions.[30]

These issues continued to remain unresolved over the years and no concrete action was taken by Members. In the recent plurilateral negotiations on e-commerce, most proposals agreed that the Moratorium should continue, including the proposals of the few participating developing countries like Brazil, China, Hong Kong, Singapore and the Republic of Korea.[31] However, the debate on whether to have a permanent moratorium is still on-going, especially in the context of revenue losses to developing countries.[32] Recently in March, 2020, although not party to the plurilateral negotiations, India and South Africa took a strong stand in the General Council. They submitted a fresh proposal arguing that the Moratorium proposes profound challenges for developing countries, both in terms of tariff revenue losses and impact on industrialization due to the loss of use of tariff as a critical trade policy instrument.[33] To counter this, they proposed that the scope of the Moratorium be limited to electronic ‘transmission’, that is the ‘carrier’, and not the content transmitted, thereby allowing countries to impose duties on electronically transmitted goods. They argued that this will ensure a reduced impact of the Moratorium on developing countries. Taking this position earlier, Indonesia has already started imposing customs duties on digitally transmitted goods such as e-books, downloadable music, software, etc.[34] It remains to be seen what stand the General Council and the Members, party to the plurilateral negotiations, will take in the future.

As we have seen above, both these cross-cutting issues are fundamental to the e-commerce discussions. Therefore, in order to make any real progress on e-commerce, both at the WTO and at the plurilateral negotiations, a resolution of these issues is imperative.

This piece has been authored by Kruthi Venkatesh, a consultant working with Ikigai Law, with inputs from Nehaa Chaudhari, Director (Public Policy), Ikigai Law.

For other articles in this series, please see here.

For more on the topic, please feel free to reach out to us at contact@ikigailaw.com.

[1] World Trade Organisation, Work Programme on Electronic Commerce, WT/L/274 (30th Sep., 1998), available at, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009-DP.aspx?language=E&CatalogueIdList=22421,14657,30467,30446,27847,31348,4101,17078,19349,3664&CurrentCatalogueIdIndex=5&FullTextHash=371857150&HasEnglishRecord=True&HasFrenchRecord=True&HasSpanishRecord=True (last accessed on 11th June, 2020).

[2] These four bodies were: Council for Trade in Services; Council for Trade in Goods; Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS) and the Committee for Trade & Development. For more context, please see our previous piece titled ‘E-commerce Related Discourse at the WTO: Brief History and Subsequent Developments’, here.

[3] World Trade Organisation, Dedicated Discussion on Electronic Commerce, General Council, WT/GC/436, 6th July, 2001, available at, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/WT/GC/W436.pdf (last accessed on 11th June, 2020).

[4] These were: (i) classification of digital products as “goods” or “services”; (ii) issues concerning developing and least-developed countries; (iii) revenue implications of e-commerce, especially for DCs; (iv) relationship between e-commerce and traditional forms of commerce to assess short-term disadvantages for DCs; (v) impact of continued moratorium on custom duties on DCs; (vi) competition related issues including constraints on e-commerce due to concentration of market power; and (vii) jurisdictional challenges for e-commerce disputes.

[5] See Sacha Wunsch-Vincent, WTO, E-Commerce and Information Technologies: From the Uruguay Round through the Doha Development Agenda, Report for the United Nations Information and Communication Technologies Task Force, pg. 15, April, 2005, available at, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/serv_e/sym_april05_e/wunschvincent_e.pdf (hereafter Sacha Wunsch-Vincent, WTO, E-Commerce and Information Technologies) (last accessed on 11th June, 2020).

[6] World Trade Organisation, Work Programme on Electronic Commerce, WT/L/274 (30th Sep., 1998).

[7] Id., at 1.

[8] López González, J. and J. Ferencz, Digital Trade and Market Openness, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 217, at 34 (2018), available at, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/1bd89c9a-en.pdf?expires=1588750001&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=2158E87D58EC0C48580BD43452E06661 (last accessed on 6th May, 2020).

[9] Id., at 14.

[10] General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, Oct. 30, 1947, 61 Stat. A-11, T.I.A.S. 1700, 55 U.N.T.S. 194 (amended by General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade 1994, Apr. 15, 1994, Annex IA, 33 I.L.M. 1154 (1994)), at art. II and III.

[11] General Agreement on Trade in Services, Apr. 15, 1994, Annex 1B, 33 I.L.M. 1167 (1994), at art. II and XVII.

[12] World Trade Organization, Work Programme on Electronic Commerce, Submission by the United States, WT/GC/16, (12th Feb., 1999) available at, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009-DP.aspx?language=E&CatalogueIdList=69278,27957,17371,23094,33968,13888,12407,24809,36846,76453&CurrentCatalogueIdIndex=8&FullTextHash=371857150&HasEnglishRecord=True&HasFrenchRecord=True&HasSpanishRecord=True [hereafter U.S. Proposal] (last accessed on 11th June, 2020).

[13] World Trade Organization, Preparations for the 1999 Ministerial Conference, Communication from Japan, WT/GC/W/253, (14th July, 1999) para 10, available at, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009-DP.aspx?language=E&CatalogueIdList=18842,11227,13715,5481,13000,10824,5444,20328,4912,7148&CurrentCatalogueIdIndex=1&FullTextHash=371857150&HasEnglishRecord=True&HasFrenchRecord=True&HasSpanishRecord=True (last accessed on 11th June, 2020).

[14] World Trade Organization, Preparations for the 1999 Ministerial Conference, Communication from the European Communities and their Member States, WT/GC/T/3 06, (Aug. 9, 1999), available at, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009-DP.aspx?language=E&CatalogueIdList=21093,61173,36798,26419,16959,32179,31670,15583,6942,10594&CurrentCatalogueIdIndex=3&FullTextHash=371857150&HasEnglishRecord=True&HasFrenchRecord=True&HasSpanishRecord=True (last accessed on 11th June, 2020).

[15] See World Customs Organization, What is the Harmonized System?, available at, http://www.wcoomd.org/en/topics/nomenclature/overview/what-is-the-harmonized-system.aspx.

[16] World Trade Organisation, Fifth Dedicated Discussion on Electronic Commerce under the Auspices of the General Council, WY/GC/W/509 (31st July., 2003), available at, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009-DP.aspx?language=E&CatalogueIdList=97269,92010,56506,57960,51701,56745,78083,2829,1038,1065&CurrentCatalogueIdIndex=8&FullTextHash=371857150&HasEnglishRecord=True&HasFrenchRecord=True&HasSpanishRecord=True (last accessed on 11th June, 2020).

[17] Id., at 1.

[18] S.A. Baker et. al., E-Products and the WTO, Vol35(1) Symposium on Borderless E-Commerce at 8, available at, https://scholar.smu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2030&context=til (last accessed on 8th May, 2020).

[19] Id., at 8.

[20] World Trade Organisation, Preparations for the 1999 Ministerial Conference, Work Programme on Electronic Commerce, Communication from Indonesia and Singapore, WTO Doc. VVT/GC/W/247, at 14 (July 9, 1999), available at, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009-DP.aspx?language=E&CatalogueIdList=18842,11227,13715,5481,13000,10824,5444,20328,4912,7148&CurrentCatalogueIdIndex=4&FullTextHash=371857150&HasEnglishRecord=True&HasFrenchRecord=True&HasSpanishRecord=True (last accessed on 11th June, 2020).

[21] For more context, please see our previous piece titled ‘E-commerce Related Discourse at the WTO: Brief History and Subsequent Developments’, here.

[22] World Trade Organisation, Ministerial Declaration on Trade in Information Technology Products, Ministerial Conference WT/MIN(96)/16 (13th Dec., 1996), available at, https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/itadec_e.pdf (last accessed on 11th June, 2020).

[23] World Trade Organisation, Ministerial Conference, Declaration on Global Electronic Commerce, Second Session WT/MIN(98)/DEC/2 (25th May, 1998), available at, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009-DP.aspx?language=E&CatalogueIdList=4814,34856,20308&CurrentCatalogueIdIndex=1&FullTextHash= (last accessed on 11th June, 2020).

[24] World Trade Organization, Work Programme on Electronic Commerce, WT/L/1079 (11th Dec., 2019), available at, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009-DP.aspx?language=E&CatalogueIdList=259703,259704,259705,259706,259710,259651,259652,259663,259304,259264&CurrentCatalogueIdIndex=5&FullTextHash=&HasEnglishRecord=True&HasFrenchRecord=True&HasSpanishRecord=True (last accessed on 11th June, 2020).

[25] UNCTAD, Growing Trade in Electronic Transmissions: Implications for the South, UNCTAD Research Paper No. 29, UNCTAD/SER.RP/2019/1/Rev.1, at 7 (Feb., 2019), available at, https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/ser-rp-2019d1_en.pdf [hereafter UNCTAD Report] (last accessed on 11th June, 2020).

[26] U.S. Proposal, supra note 13, at 2.

[27] Sacha Wunsch-Vincent, WTO, E-Commerce and Information Technologies, supra note 5, at 140.

[28] UNCTAD Report, supra note 26, at 27.

[29] Id., at 27.

[30] Sacha Wunsch-Vincent, WTO, E-Commerce and Information Technologies, supra note 5, at 141.

[31] See Katya Garcia-Israel and Julien Grollier, Electronic Commerce Joint Statement: Issues in the Negotiations Phase, CUTS International, at 9 (Oct., 2019), available at, http://www.cuts-geneva.org/pdf/1906-Note-RRN-E-Commerce%20Joint%20Statement2.pdf (last accessed on 11th June, 2020).

[32] Yasmin Ismail, E-commerce in the World Trade Organization: History and latest developments in the negotiations under the Joint Statement, International Institute for Sustainable Development, at 17, (Jan., 2020), available at, https://www.iisd.org/sites/default/files/publications/e-commerce-world-trade-organization-.pdf (last accessed on 11th June, 2020).

[33] World Trade Organization, Work Programme on Electronic Commerce, Communication from India and South Africa, WT/GC/W/798 (11th Mar., 2020), available at, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009-DP.aspx?language=E&CatalogueIdList=262031,254708,240766,240755,240689,240551,240484,240132,239982,239968&CurrentCatalogueIdIndex=0&FullTextHash=371857150&HasEnglishRecord=True&HasFrenchRecord=True&HasSpanishRecord=True (last accessed on 11th June, 2020).

[34] See Y.K. Hartono, Welcoming Import Duties on Intangible Goods, The Jakarta Post, 10th January, 2018, available at, https://www.thejakartapost.com/academia/2018/01/10/welcoming-import-duties-on-intangible-goods.html (last accessed on 11th June, 2020).