The simplest of wearable fitness devices consist of a tiny accelerometer embedded deep within an integrated circuit board, wrapped in lithium polymer and encased in a polycarbonate case. Accelerometers can measure small changes in acceleration force and orientation, and can sense if it is in a horizontal or vertical position, and whether it is in motion or at rest. The data received from it is analysed to calculate a multitude of information – How long did one walk? How long was one sitting? How much quality sleep did one get?

Wearable devices – mostly in the form of fitness bands – have seen rapid growth in the consumer market. Correspondingly, sales of these devices, particularly in the low-budget segment, have also skyrocketed as consumers have embraced healthy living and affordable devices that enable them to achieve their basic fitness goals.

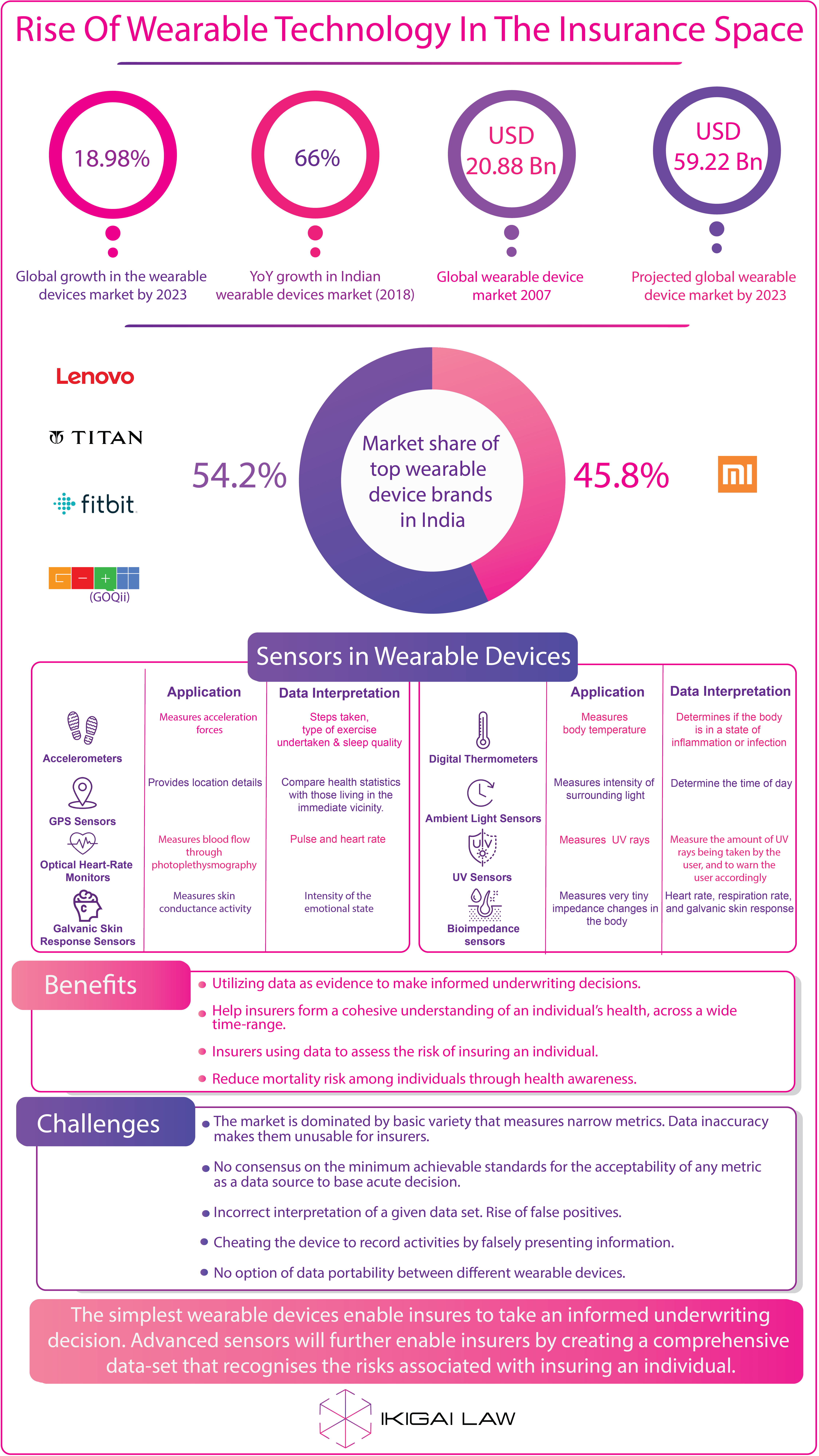

The global wearable devices market is expected to reach 59.22 billion USD by 2023 from 20.88 billion USD in 2017 with a CAGR of 18.98% during the period[1]. The Indian wearable devices market witnessed an impressive growth in the second quarter of 2018 (2018Q2) as the overall wearable devices market grew 66% year-over-year and 40% sequentially. The top brands in India is led by Xiaomi (with a 45.8% market-share), followed by GOQii, Titan, Fitbit and Lenovo.[2]

There is now a massive database of fitness and health metrics that are being continuously collected, and stored by fitness apps on a real-time basis. But while this data is of particular use to the users, it can also be used to compute an understanding of the collective health of populations, the vigour of their activities, and their daily habits. The data collected from wearable devices can be specific to those groups of people who have been geographically ring-fenced; which would make such data less generic as it would then pertain to a specific population living under known climatic conditions. This also allows for more meaningful comparison between an individual’s fitness levels with those who are existing within the same geographical and climatic boundaries.

Wearable devices are quickly moving past merely relying on accelerometers, and have introduced intensely sophisticated technology to capture even more varied metrics. Many midrange and top-range wearable devices now contain GPS chips, Optical Heart-Rate Monitors, Galvanic Skin Response Sensors, Digital Thermometers, Ambient Light Sensors, UV Sensors, Bioimpedance sensors, Constant Glucose Monitoring (CGM) sensors; and the list is expected to get even longer.

Consequently, the wearable devices market is far from being homogenous, at least as far as technology is concerned; and data reliability is a major concern when it comes to data assimilated across a population when it is based on non-homogenous technical qualities of wearable device.

The information from wearable devices, and the ability to have non-generic data, is of particular interest to insurance companies, because there is a direct link between this data, and the health of the person the insurance company is about to insure.

Till very recently, health and life insurance has been a subject matter of representations and statements from the insured, and a medical check-up, when necessary. Getting an insurance meant having to go through an insurance agent, who would visit with standard format questionnaires seeking personal health data. The questionnaires would be filled in by the insurance agent on the basis of verbal information given by the customer. To check the veracity of the disclosures made, insurers would sometimes also require a health check-up of the individual.

Insurance coverage is granted in such cases on the basis of a one-time assessment. A longer-term or a continuous assessment mechanism may have presented the insurer with a more nuanced data-set to base its underwriting decisions upon.

Also, the data collected using self-declaration may be inadequate for an insurer from a risk-assessment perspective. This is particularly so in the case where chances of misrepresentation to secure a lower premium is high.

To address the pitfalls of traditional information collection and assessment mechanisms, insurance companies are turning to technology to rapidly turn around a legacy industry; and wearable devices are increasingly playing a significant part in this turnaround as they provide a comprehensive and continuous health data from customers.

Wearable devices speak to health insurers giving them the opportunity to better analyse the risks associated with insuring particular individuals. Data from these devices can be used as a source of evidence to make informed underwriting decisions.

Decisions can be based on the range of metrics – many of them emerging metrics based on newer and more advanced sensors.

Insurance companies already have substantial health data of their customers – in the form of medical files, doctor’s prescriptions, etc. – and the data collected from wearable devices are only marginal to their decision-making process. However it can provide a secondary base to appraise insurers of the risks and benefits of insuring specific individuals, and enable insurers to provide appropriate insurance coverage to its customers.

But the going isn’t smooth just yet. A majority of the wearable devices being sold are of the very basic variety that can only measure very limited metrics, and are plagued with inaccuracy issues. Secondly, there is still no consensus amongst insurers on the minimum standards that must be achieved before any metric is acceptable as a data source on which acute decisions can be based upon.

That means insurers currently do not have enough reliable data to create a comprehensive base upon which they can compare individual health data metrics. Incomplete metrics – particularly because basic devices do not have sensors that can measure them – give rise to dark-spots that become impossible to fill. This is particularly so in the developing world where income inequality pushes large swathes of the population towards basic wearable devices, and these dark-spots are even more apparent. Insurers in these territories will face greater hurdles to assimilate credible data from such basic devices.

In more developed markets, where mid-to-advance-level wearable devices are abound, the challenge is in being able to correctly interpret a given data set. For example, while certain wearable devices can identify smoker behaviour by identifying the hand movement of bringing a cigarette to the mouth, the same can also be as a result of a false positive – as in the case where the embedded software mistakes a cup of coffee to be a cigarette. This would unfairly penalise a user.

The third, and very obvious, challenge is the ability to cheat the device to make it record activities that have not actually been undertaken by the user. Discipline among users – in respect of their association with their devices – is also a concern, as well as shifting from one brand to another without the option to port already existing past data into the new system.

Given these challenges, it could be years before an adequate data-pool is achieved that would contain enough meaningful empirical data to create a comprehensive insight into health metrics – both on a societal as well as on an individual level.

Undaunted by the challenges however, many insurers are offering wearable devices along with their insurance products, spurring their customers to use them as a tool to take stock of their health and wellness. It is in the interest of the insurers, and as well as the insured, to ensure that the insured be healthy, and with a lower mortality risk. To that extent, many insurers are perfectly satisfied with being able to merely measure and monitor the number of steps taken by their customers; and it is something that even the simplest of wearable devices can detect adequately well.

This post has been authored by Sayanhya Roy, Principal Associate, Ikigai Law

For more on the topic, please feel free to reach out to the author at: sayanhya@ikigailaw.com.

Disclaimer: This article is meant for general informational purpose only and is not a substitute for professional legal advice.

References

[1] https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20181206005489/en/Global-Fitness-Tracker-Market-Opportunities—Forecast

[2] https://www.idc.com/tracker/showproductinfo.jsp?prod_id=962