This article traces how courts across India have interpreted some crucial concepts pertaining to Safe Harbour law in India.

It is Part II in our series of articles which trace the evolution of Safe Harbour law in India. You can read Part I of this series here.

To recap– in the on-line world, Safe Harbour provisions protect the people and enterprises who provide the underlying infrastructure (also known as intermediaries), from liability for the acts of third parties who use this infrastructure for their own purposes. For e.g. Internet Service Providers (ISPs) are not liable if their subscribers use the internet for unlawful acts, Cloud Service Providers (CSPs) are not liable because people store illegal data on their server, e-commerce platforms are not liable if people sell spurious goods, and social media platforms are not liable if people post defamatory content.

Safe Harbour provisions for intermediaries in India are found under the Information Technology Act, 2000 (“IT Act”) and its corresponding rules. The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines) Rules, 2011 (“Intermediary Guidelines”)[1] are the primary guidelines which intermediaries need to observe to avail safe-harbour protection.

The Safe Harbour rules have evolved considerably since their enactment, partly through amendments of the underlying act and rules, and partly through the way in which these provisions are interpreted by the Court.

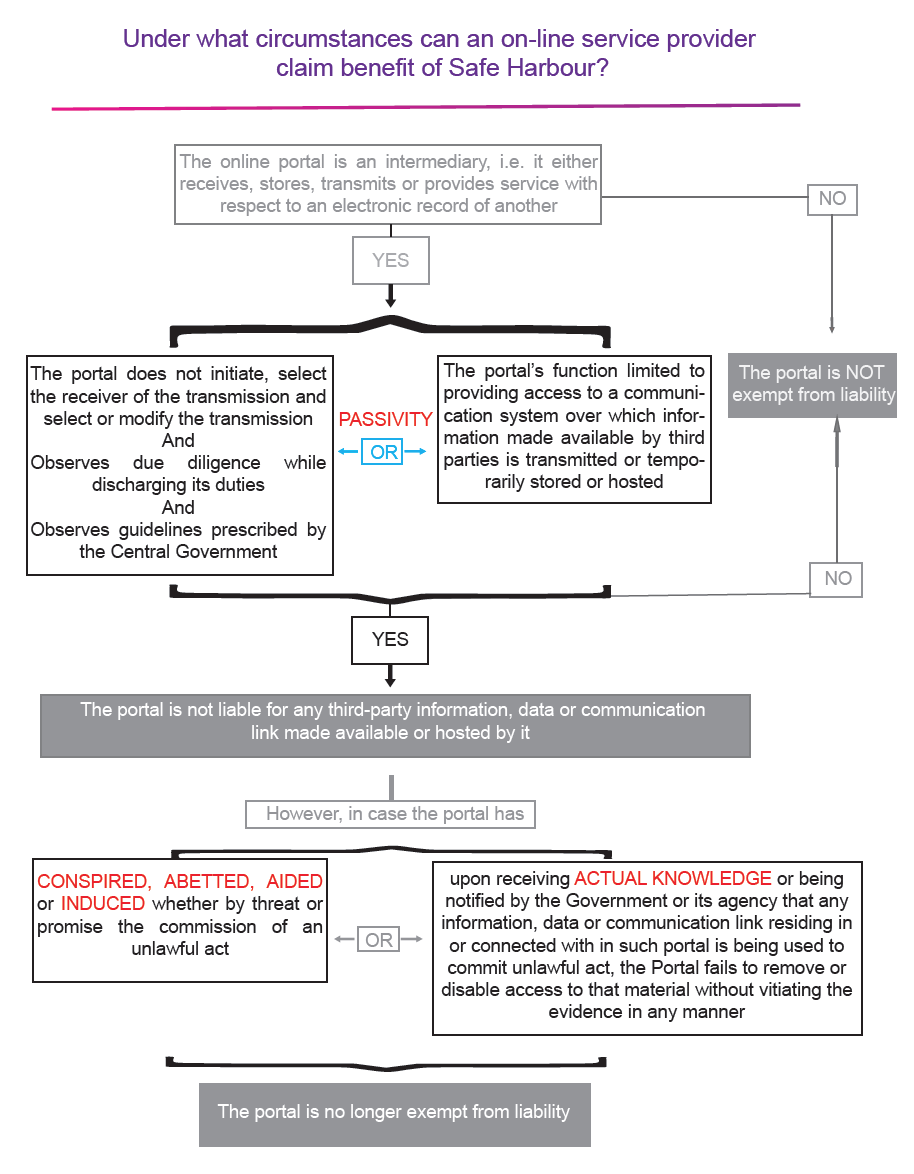

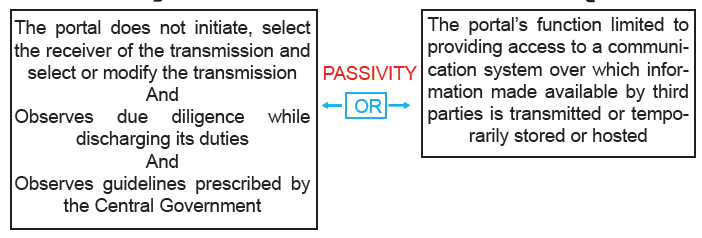

The current provisions in relation to Safe Harbour protection for intermediaries are summarised in the diagram below. We will be analysing the highlighted section which deal with the concepts of (i) passivity; (ii) aiding or abetting the commission of an unlawful act and (iii) actual knowledge.

(i) Passivity

The Safe Harbour protection under Indian law extends only to “passive” intermediaries, i.e. intermediaries which “act as mere conduits or passive transmitters of the records or information[2]”. Thus, unless an intermediary confines itself to a technical role wherein it provides automated or technical processing of data provided by its user, it will lose its immunity. To claim this immunity an intermediary is not expected to do anything which gives it knowledge of or control over user generated data.

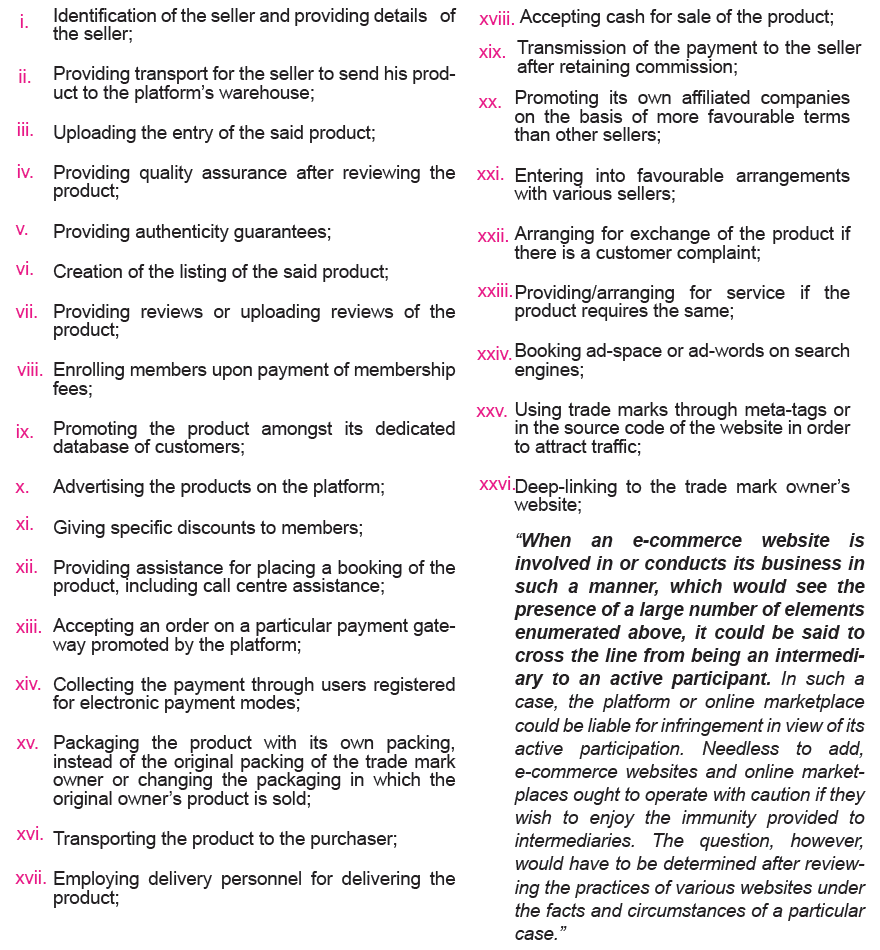

In the matter Christian Louboutin SAS vs Nakul Bajaj and Ors[3], the Delhi High Court provided some insight on what it means to be a passive transmitter of information. It made an exhaustive list of various functions that may be performed by an intermediary and held the more functions an intermediary performs the more likely it is to be termed as an active participant. The list populated by the Delhi High Court is as under-

Factors enumerated in Christian Louboutin judgement have been used by the Delhi High Court to determine whether certain online marketplaces are amenable to Safe Harbour protection as under-

| Website in question– Shopclues.com[4] | |

Grounds for claiming Safe Harbour

|

Factors going against

|

| What the court held-The Court held that www.shopclues.com would not qualify for Safe Harbour protection. | |

| Website in question– Kaunsa.com[5]

|

|

Grounds for claiming Safe Harbour

|

Factors going against

|

| What the court held-The Court held that www.kaunsa.com would not qualify for Safe Harbour protection. | |

Key Takeaways- To claim safe harbour protections intermediaries –

- Make any personal guarantee or warrantee regarding the authenticity, quality etc. of the products/services offered by third party on their website.

- Have a real and effect grievance redressal policy in place, to handle complaints of consumers and merchants including for IP infringement. This must not be a mere eyewash but should provide effective redressal to complaints.

The approach taken by the Delhi High Court stands in contrast to the approach taken by the Bombay High Court on similar matter, which has in several cases held that as long as the intermediaries co-operate with the rights holders and provide them relevant information of the infringing sellers[6].

(ii) Aiding or Abetting the commission of an unlawful act

Where an intermediary is charged with conspiring, aiding, abetting or inducing an unlawful act, the provisions of the law the violation of which the intermediary has been charged with have to be seen. For instance, if the products listed by a vendor on an e-commerce website are charged as being counterfeit and thus infringing on the trademark of the original manufacturer the provisions of the Trademarks Act, 1999 will be referred to. Section 101 and 102 of the said Act state the meaning of applying trademark and trade description and falsely applying trademarks respectively. Basis these provisions of the Trademark Act, the Delhi High Court was of the opinion that any-

- online marketplace or e-commerce portal which allows storing of counterfeit goods;

- service provider who uses the mark in an invoice and thereby gives the impression that the counterfeit product is a genuine product;

- service provider who displays advertisement of the mark on the website so to promote counterfeit products;

- service provider who encloses the counterfeit product with its own packaging

would be deemed to have aided in the infringement or falsification of the mark[7].

(iii) Actual Knowledge

Rule 3 (2) of the Intermediary Guidelines stipulates that intermediaries are required to inform their users not to host, display, upload, modify etc. information of the nature mentioned under that rule. Rule 3(4) is the takedown provision which states that any information which is in contravention of Rule 3 (2) must be disabled by an intermediary within thirty-six hours of “obtaining knowledge by itself or [receiving] actual knowledge by an affected person in writing ….”. The effect of this provision was that any person aggrieved by any content displayed on the intermediary platform could simply send a written request to the intermediary to take down such content as it was unlawful. The intermediary would then within the next 36 hours have to apply its own judgment to determine whether the content was unlawful or not. Consequently in instances where the intermediary felt that there was the slightest possibility that the content might be deemed to be unlawful it would be compelled to take down the content within 36 hours of receiving the written communication or risk losing the safe harbour protection.[8] Hence, intermediaries started to readily removed content pursuant to civilian requests to avoid risking loss of safe-harbour protections[9].

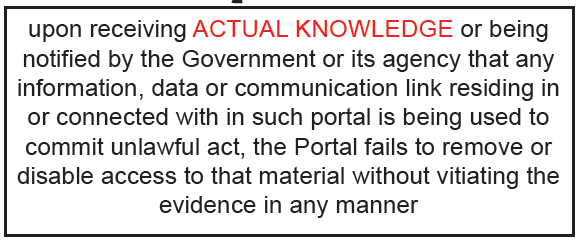

This problem was remedied by the Supreme Court in 2015, through the Shreya Singhal Case. The Supreme Court held that an intermediary was bound to take down and unlawful content on its platform only upon receiving “actual knowledge from a court order or on being notified by the appropriate government or its agency that unlawful acts relatable to Article 19(2) are going to be committed”[10]. Similarly, “actual knowledge” as used in Rule 3(4) was read down to mean knowledge through the means of a court order. Thus, an intermediary would no longer lose safe harbour protection if it refused to take down content on its platform pursuant to a written intimation by any party that the concerned content was unlawful. It was only bound to take down content pursuant to an order of a court or upon being notified by the appropriate government or its concerned agency.

Meanwhile, Super Cassettes Industries Ltd. sued MySpace Inc. for alleged copyright infringement of its content on the latter’s platform. This was also known as the MySpace Case. A 2011 interim order[11] passed by a single bench of the Delhi High Court held MySpace liable for copyright infringement despite MySpace showing that it had no knowledge of the infringement on its platform, that it removed infringing material upon receiving complaints and that Super Cassettes had refused to submit songs to MySpace’s song ID database. The interim order also directed MySpace to pre-screen all user-uploaded content.

This interim order was subsequently overruled by a division bench of the Delhi High Court[12], which observed that MySpace could only be said to have general awareness and not actual knowledge of the infringement[13]. Further, the Court observed that in the case of copyright laws it is sufficient that MySpace receives specific knowledge of the infringing works in the format provided for in its website from the content owner without the necessity of a Court order”[14]. Thus, the Delhi High Court carved out an exception to the ruling of the Supreme Court in the Shreya Singhal case, wherein the Supreme Court had held that a platform is deemed to have actual knowledge about the illegality of any content hosted on such platform only when such information is communicated to the Platform by way of a court order.

Global Takedowns- In its recent judgment[15], the Delhi High Court has held that the requirement imposed on intermediaries to take down any content under section 79 of the IT Act implies that the intermediaries have to remove such content from their entire computer network, wherever it may be located across the world, and not merely in India. Thus, all material which is deemed to be unlawful content as per Indian Law, is required to be taken down by the concerned intermediary platform globally (if it has the technical capability to do so) and not just in India. Our in-depth analysis of this order is available here.

Conclusion

Based on the above discussion there are certain mitigative measures which an intermediary can deploy to avoid losing safe harbour cover. These include-

- Have a clear and effective grievance redressal policy in place, through which users or merchants can file complaints (especially in relation to IP infringement). Remember this policy is not there just for optics. You must put processes in place to ensure that the complaints are investigated and acted upon.

- Do not make any statements guarantying the products and/or services provided by other on your website.

- There should be a mechanism in place through which details of the offending merchant on your platform can be provided to the complainant. Remember you are just providing the platform on which your users transact with the vendors/merchants who offer goods and services on your platform. In case of any dispute your policies and terms should be designed in such a way that you can put these two parties in direct contact with each other and bow out.

- As far as possible invoices should be raised only by the merchants/vendors selling goods/service on your website and not by you. It might be worthwhile if you can get them to use their own packaging as well.

We understand that it would be difficult for intermediaries to put in place several of these measures. They will affect the quality of service they offer to their vendors and their branding practices. However, unless the law relating to Safe Harbour is amended to give more space to intermediaries to perform their support and logistical activities their ability to perform these activities will continue to be severely restricted.

Unfortunately, the proposed amendments to Safe Harbour provisions seek to impose greater restrictions on intermediaries. Certain measures, such as obligation to monitor and filter content, appear to be contrary to the very concept of an intermediary being a passive transmitter of information. You can read more about our analysis of the proposed amendments here.

Intermediaries serve a useful purpose in the society and the economy by creating new marketplaces and avenues for people to transact. It has been seen that strong Safe Harbour protection laws allow intermediaries to focus on improving and expanding scope of services without worrying about legal action[16]. On the contrary, laws that do not provide adequate cover to intermediaries discourage service providers from offering a service[17]. The need of the hour is to provide greater support and flexibility to intermediaries to carry out their functions. This is not being achieved either by the current law or the draft amendments.

Authored by Tanya Sadana, Principal Associate Ikigai Law with inputs from Anirudh Rastogi

[1] The Intermediary Guidelines were released by the Department of Information Technology, Ministry of Communication Technology vide G.S.R. 314(E) dated 11 April 2011, in exercise of the powers conferred by clause (zg) of sub-section (2) of Section 87 read with sub-section (2) of section 79 of the Information Technology Act, 2000. The Intermediary Guidelines are available at https://www.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/en/in/in099en.pdf (Last accessed on 02 April 2019).

[2] Christian Louboutin SAS vs Nakul Bajaj and Ors. (2014 SCC OnLine Del 4932) para 43

[3] Christian Louboutin SAS vs Nakul Bajaj and Ors. (2014 SCC OnLine Del 4932)

[4] Skulllcandy Inc. vs. Shri Shyam Telecom and Ors. (CS (COMM) 976 of 2016) & L’Oreal vs. Brandworld and Ors (CS (COMM) 980 of 2016)

[5] Luxottica Group S.P.A. and Ors. vs. Mify Solution Pvt. Ltd. And Ors. (CS(COMM) 453 of 2016)

[6] Sidhi Vinayak Knots & Prints Pvt. Ltd. & Anr vs Amazon India & Anr. (2017 SCC OnLine Bom 6380); Metro Shoes Ltd. & Anr. Vs. Tplexo Online Pvt. Ltd. & Anr (2016 SCC OnLine Bom 9998);

[7] Para 80, Christian Louboutin SAS vs Nakul Bajaj and Ors. (2014 SCC OnLine Del 4932)

[8] This observation was made in Shreya Singhal v. Union of India, Para 117, MANU/SC/0329/2015 (Supreme Court of India).

[9] Nikhil Pahwa, #NAMApolicy on Safe Harbor: Should different sizes or categories of intermediaries be regulated differently? (05 February 2019), available at

https://www.medianama.com/2019/02/223-regulation-of-intermediaries-nama/?fbclid=IwAR1IUx2a20Gc2cGbyO4lQaLiNjHrBiG7B5H3eTxr22a2gBQUPf6zOtY0d7Q (Last accessed on 02 April 2019).

[10] Shreya Singhal v. Union of India, Para 119, MANU/SC/0329/2015 (Supreme Court of India).

[11] Super Cassettes Industries Ltd. vs Myspace Inc. & Anr., 2011 SCC OnLine Del 3131 (Delhi High Court).

[12] Myspace Inc. v. Super Cassettes Industries Ltd., MANU/DE/3411/2016 (Delhi High Court).

[13] Myspace Inc. v. Super Cassettes Industries Ltd., Paras 68 & 69, MANU/DE/3411/2016 (Delhi High Court).

[14] Myspace Inc. v. Super Cassettes Industries Ltd., Paras 50, MANU/DE/3411/2016 (Delhi High Court).

[15] Swami Ramdev and Anr. vs. Facebook Inc. & Ors, CS(OS) 27 of 2019 available at http://lobis.nic.in/ddir/dhc/PMS/judgement/23-10-2019/PMS23102019S272019.pdf

[16] https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/documents/GCIG%20no.42.pdf

[17] For instance, public Wi-Fi in Germany was unavailable untillThe example of public Wi-Fi in Germany helps dramatize the relationship of intermediary liability and the decision to offer a service. It has long been difficult to find public Wi-Fi in Germany. This is not for lack of technology in the country, but rather because of the law making Wi-Fi intermediaries liable for the actions of their users: “Private hotspot providers in Germany are liable for the misconduct of users. If, for example, a user were to download music or a movie on a particular hotspot, the provider ran the risk of being sued for piracy” (Brady 2016).