This is a quick guide to the evolution of safe harbour provisions under Indian Law and how proposed amendments are likely to impact them.

If you wish to skip the history of safe harbour provisions under Indian Law and want to learn about the the current safe harbour framework, please see our visual guide here.

If you are well-versed with existing framework and want to learn about proposed changes to the safe harbour framework, you can jump straight to our assessment of the likely impact of the proposed amendments, available here.

In the on-line world, Safe Harbour provisions protect the people and enterprises who provide the underlying infrastructure, also known as intermediaries, from liability for the acts of third parties who use this infrastructure for their own purposes. For e.g. Internet Service Providers (ISPs) are not liable if their subscribers use the internet for unlawful acts, Cloud Service Providers (CSPs) are not liable because people store illegal data on their server, e-commerce platforms are not liable if people sell spurious goods, and social media platforms are not liable if people post defamatory content.

Safe Harbour provisions for intermediaries in India are found under the Information Technology Act, 2000 (“IT Act”) and its corresponding rules. The Safe Harbour rules have evolved considerably since their enactment, partly through amendments of the underlying act and rules, and partly through the way in which these provisions are interpreted by the Court.

Through these articles we will be mapping the course of this evolution and highlighting the benefits and pitfalls we see in the existing and proposed Safe Harbour provisions.

This article traces the development of the statutory law. Part II of this series will focus on judicial interpretation of safe harbour provisions in India.

Stage I – 2000- 2008

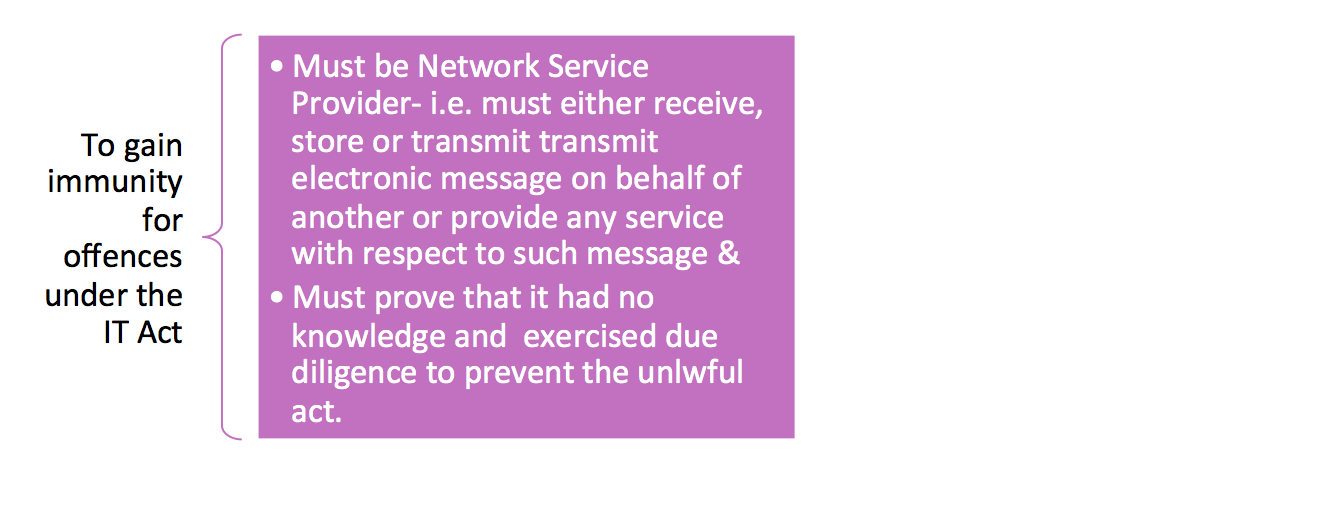

In its original form, the IT Act provided little to no Safe Harbour protection to internet intermediaries.

For starters the definition of intermediaries[1] was restricted only to those entities who on behalf of another person receives, stores or transmits any electronic message or provides any service with respect to that message.

Even the intermediaries who qualified within this narrow definition were shielded only with respect to offences defined under the IT Act and not any other law[2].

These limited provisions provided little to no protection to an online intermediary. These shortcomings were highlighted in 2004 when a CD containing an obscene clip was posted[3] for sale by a user on the online auction site bazee.com. As a result of this, both the user, Mr. Ravi Raj and the CEO of bazee.com, Mr. Avnish Bajaj, were arrested and charged with the same offence. This case highlighted the lacuna in law, whereby an intermediary could be exposed to liability on account material it did not generate but only provided a platform to publish/circulate. The possibility of such liability threatened the growth of the e-commerce ecosystem. Accordingly, the Information Technology (Amendment) Act, 2008[4] was introduced which, amongst others broadened the scope of Safe Harbour Protection available to intermediaries.

Stage II- Current Safe Harbour provisions

Presently the definition of an ‘intermediary[5]’ has been broadened to include “any person, who on behalf of another person, receives, stores or transmits any particular electronic record or provides any service with respect to that record.” Telecom service providers, network service providers, internet service providers, web-hosting service providers, search engines, online payment sites, online-auction sites, online-market places, cyber cafes and interactive websites such as Facebook, Twitter, Blogspot and WordPress are all considered intermediaries as per this definition[6].

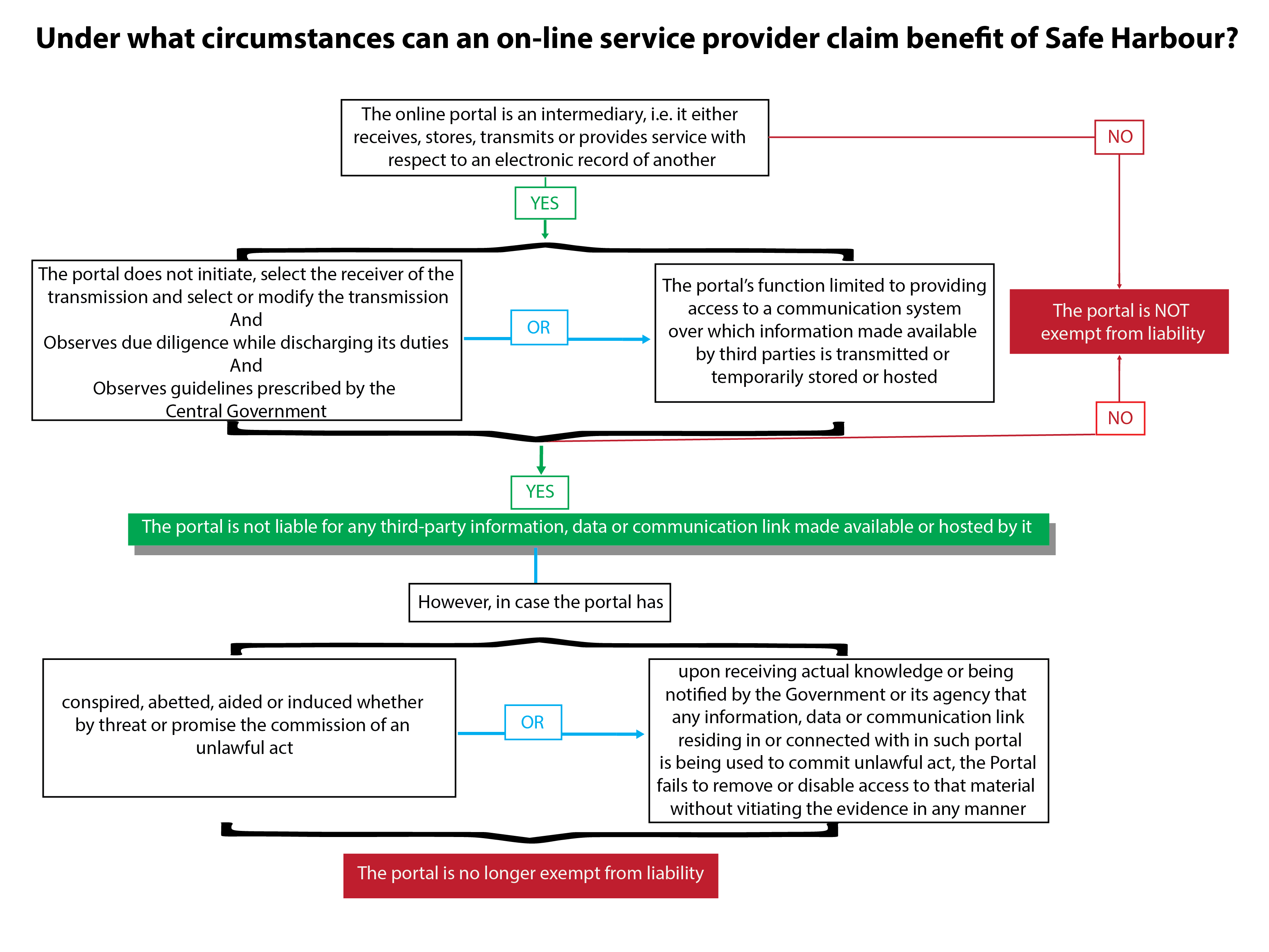

Safe Harbour provisions are found under Section 79 of the Information Technology Act, 2000 (“IT Act”)[7]. Section 79 (2) lists out the requirements to avail safe-harbour protection. One of these requirements is the observance of guidelines prescribed by the central government from time to time. The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines) Rules, 2011 (“Intermediary Guidelines”)[8] are the primary guidelines which intermediaries need to observe to avail safe-harbour protection. These guidelines list out the due diligence requirements that must be observed by intermediaries to avail the safe-harbour protection.

The current framework for safe-harbour protection in India is illustrated in the flow-chart below.

| Advantages over erstwhile Safe Harbour Provisions | Areas of Concerns |

|

Particularly, the stipulation that that intermediaries should not “initiate, select the receiver of the transmission and select or modify the transmission”, is unduly harsh.

The purpose and function of an intermediary is to facilitate transaction and/or transmission of data initiated by their users. This would in many instances, necessarily involve structuring the environment in which such transactions and/or transmissions take place. This is especially crucial for e-commerce intermediaries operating in new markets wherein the sellers may lack the technical skills/knowledge to optimise the display of the information relating to their products. Even in developed markets certain activities undertaken by intermediaries such as indexing of content, targeted advertising based on user preferences etc., enrich user experience and are considered indispensable.

For more on this please refer to our discussion around passivity and the observations made by Delhi High Court’s in Christian Louboutin SAS vs Nakul Bajaj and Ors. (2014 SCC OnLine Del 4932) in Part II of this Series. |

For more on this please refer to our discussion around the interpretation of the terms “actual knowledge” in Part II of this Series.

|

|

For more on this please refer to our discussion around Global Takedowns in Part II of this Series. |

Stage III- Proposed Amendments to Intermediary Guidelines

The proposed amendments to the Safe Harbour provisions amend the Intermediary Guidelines alone and do not change any provision of the IT Act itself. Nevertheless, they impose far reaching onerous provisions which an intermediary must comply with to claim Safe Harbour protection. These have been summarised and contrasted with the corresponding earlier requirements below-

| Current Obligation | Proposed Obligation | Concerns with Proposed Obligation |

| Terms of Use: Intermediaries are required to publish rules and regulations, privacy policy and/or user agreement for use and access to their portals.

Such Rules must warn users not to publish certain type of content which has been listed (“Prohibited Content”) in the Intermediary Guidelines. |

Terms of Use: The list of Prohibited Content will be expanded to include content which promotes consumption of tobacco or intoxicating products and content which threatens the critical infrastructure of India.

An intermediary is now also required to warn its users at least once a month, of their need to comply with the intermediary’s terms of use.

|

|

| No equivalent requirement in current Intermediary Guidelines. | Mandatory Assistance to State Agencies: Intermediaries are required to provide assistance requested by “any government agency”, within 72 hours of such request being made. This request may be for the security of the State; cyber security; the purpose of investigation, detection, prosecution or prevention of offence, or for protective or cyber security and matters connected with or incidental thereto.

|

|

| Trace the publisher of information: The intermediaries, upon receiving a request by the authorised agency, will be required to trace the originator of any information. |

|

|

| Local Presence Requirement: Intermediaries with above 50 Lakh users are required to be incorporated in India and permanent, registered, physical address in India. They are also required to have a nodal person who shall be available 24X7 to provide assistance to State agencies. |

|

|

| Take-Down Requirement: Intermediaries are required to take-down Prohibited Content within 36 hours of receiving “actual knowledge” of the existence of such content on their platform. They are required to preserve records relating to such content for 90 days to facilitate investigation. | Take-Down Requirement: Intermediaries are required to take-down content only upon receiving actual knowledge by way of a court order or upon being notified by appropriate government agency.

Courts or Government agencies may order content to be taken-down only if such content is not in the interest of the sovereignty and integrity of India; security of the State; friendly relations with other States; public order, decency or morality; or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement of any offence. Such take-down must occur within 24 hours of the receipt of the order and/or notification. The intermediary will have to preserve the records for a minimum of 180 days.

|

|

| No equivalent requirement in current Intermediary Guidelines. | Proactive Monitoring of Content: Intermediaries are required to deploy technology based automated tools or appropriate mechanisms with appropriate controls to proactively identify and remove access to unlawful content. |

|

Authored by Tanya Sadana, Senior Associate Ikigai Law with inputs from Anirudh Rastogi and Aman Taneja.

References –

[1] Previous text of Section 2(w) of the IT Act was :- “(w) “intermediary”, with respect to any particular electronic message, means any person who on behalf of another person receives, stores or transmits that message or provides any service with respect to that message;”

[2] Previous text of Section 79 of the IT Act was was :- “Section79 : Network service providers not to be liable in certain cases:- For the removal of doubts, it is hereby declared that no person providing any service as a network service provider shall be liable under this Act, rules or regulations made thereunder for any third party information or data made available by him if he proves that the offence or contravention was committed without his knowledge or that he had exercised all due diligence to prevent the commission of such offence or contravention.

Explanation.—For the purposes of this section,—

(a) “network service provider” means an intermediary;

(b) “third party information” means any information dealt with by a network service provider in his capacity as an intermediary.”

[3] Avnish Bajaj v. State, Para 6, MANU/DE/1357/2004 (Delhi High Court).

[4] Available at http://nagapol.gov.in/PDF/IT%20Act%20(Amendments)2008.pdf (Last accessed on 02 April 2019).

[5] Section 2(w) of the IT Act

[6] Intermediaries, users and the law – Analysing intermediary liability and the IT Rules, Pages 3 & 4, Software Freedom Law Centre, available at https://sflc.in/sites/default/files/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/eBook-IT-Rules.pdf (Last accessed on 31 March 2019).

[7] The Information Technology Act, 2000 was enacted by the then Ministry of Law, Justice and Company Affairs vide Extraordinary Gazette publication dated 9 June 2019. The IT Act is available at https://indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/1999?view_type=browse&sam_handle=123456789/1362 (Last accessed on 2 April 2019).

[8] The Intermediary Guidelines were released by the Department of Information Technology, Ministry of Communication Technology vide G.S.R. 314(E) dated 11 April 2011, in exercise of the powers conferred by clause (zg) of sub-section (2) of Section 87 read with sub-section (2) of section 79 of the Information Technology Act, 2000. The Intermediary Guidelines are available at https://www.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/en/in/in099en.pdf (Last accessed on 02 April 2019).

[9] Shreya Singhal v Union of India, WP(Cr) No. 167 of 2012

[10] J. Malcolm, Users Around the World Reject Europe’s Upload Filtering Proposal, available at https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2016/11/users-around-world-reject-europes-upload-filtering-proposal.

[11] In Sabu Mathew George v. Union of India, (2017) 7 SCC 657, it was submitted by the respondent intermediaries that content which violated the PCPNDT Act could be removed only upon being brought to their notice. Even such limited blocking has not seen much success; Legally India, Roundup of Sabu Mathew George vs. Union of India: Intermediary liability and the ‘doctrine of auto-block’, available at https://www.legallyindia.com/views/entry/roundup-of-sabu-mathew-george-vs-union-of-india-intermediary-liability-and-the-doctrine-of-auto-block.